Racist “Karen” goes on drunken rant in Barrow County

By Joe Johnson

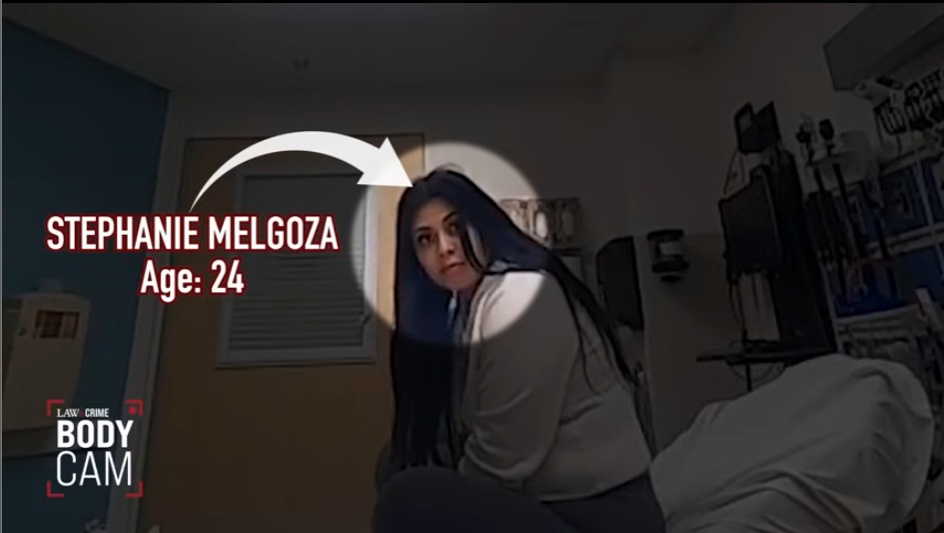

A woman was arrested at Holiday Inn Express in Bethlehem after falsely accusing a man of assaulting her in a drunken escapade,

Winder Police said Amy Baxter, 32, called 911 multiple times to report the alleged assault but continually hung up when asked for information. Police tracked her down to the hotel where she had earlier been given a courtesy ride to by officers due to her extreme intoxication.

Staff told police she caused a scene in the lobby even pointing to a guest who had just arrived to check in, accusing him of being the attacker. But when police asked Amy to describe the suspect, she was reluctant to speak with the African-American sheriff’s deputy.

Watch the incident unfold in the video below:

“You Have to Move!”

The Cruel and Ineffective Criminalization of Unhoused People in Los Angeles

Police remove an unhoused woman from her tent during a sanitation sweep in Los Angeles, October 2023. © 2023 Anthony Orendorff, StreetWatch

Summary

Adequate housing is an internationally protected human right. But the United States, which has been treating housing primarily as a commodity, is failing to protect this right for large numbers of people, with houselessness a pervasive problem. In the US city of Los Angeles, California, where the monetary value of property has risen to extreme heights while wages at the lower end of the economic spectrum have stagnated for decades, houselessness has exploded into public view. Policymakers addressing the issue publicly acknowledge the necessity of increased housing to solve houselessness, but their primary response on the ground has been criminalization of those without it.

The criminalization of houselessness means treating people who live on the streets as criminals and directing resources towards arresting and citing them, institutionalizing them, removing them from visible public spaces, denying them basic services and sanitation, confiscating and destroying their property, and pressuring them into substandard shelter situations that share some characteristics with jails. Criminalization is expensive, but temporarily removes signs of houselessness and extreme poverty from the view of the housed public. Criminalization is ineffective because it punishes people for living in poverty while ignoring and even reaffirming the causes of that poverty embedded in the economic system and the incentives that drive housing development and underdevelopment. Criminalization is cruel.

Criminalization effectively destroys lives and property based on race and economic class. It is a set of policies that prioritizes the needs and values of the wealthy, property owners, and business elites, at the expense of the rights of people living in poverty to an adequate standard of living. As a consequence of historical and present policies and practices that discriminate against Black and other BIPOC people, these groups receive the brunt of criminalization.

Read a text description of this video

[Text]

Over 75,000 people are without housing in the county of Los Angeles.

The city has authorized LA Sanitation to conduct systematic clearings of unhoused encampments, enforced by the Los Angeles Police Department.

The operations are known as ‘sweeps.’

Numbers of unsheltered residents continue to increase as wages fall far behind the cost of housing.

Six unhoused people die every day in LA County.

swept

part one

[We see a small encampment next to a canal.]

MICHELLE: They woke us up this morning telling us that they’re going to do a clean sweep, and that to grab what we can, and to get out. Because they were taking everything else.

They take our food. They took all my underclothes. They took all my shoes. They leave us with no resources. So we’re stuck here until we can manage to get something to eat or clean water or whatever it is, because they don’t care.

I’ve been here four years on the river, and they’ve done this to us three times already.

Everybody gets to arguing.

Everybody gets to fighting.

Your relationship falls apart.

Your family falls apart.

I was a manager of a laundromat. The minute Covid hit the owner he was gone. Took all the money from all the machines. He left me there with nothing. I lost my job, I lost my house. It’s mainly me, my family. My son, my boyfriend, my friend.

This is our home right here. Because we’re together. I feel like I’m the mom. Everybody comes to me, like, “What are we going to do? What are we going to do?” I don’t know anymore.

If we don’t stick together… we won’t make it.

PETE WHITE, Los Angeles Community Action Network: Over the last decade here in Los Angeles, houselessness has exploded.

The city has made the choice to use criminalization and sweeps as the answer to houselessness.

Criminalization, in the most simple sense, is the use of laws and policies and regulation to arrest, displace and banish poor people

from places that government does not want to see them.

BECKY DENNISON, Venice Community Housing: I cannot answer the question as to why Los Angeles, or any other locality would still be using a criminalization model. It clearly does not work.

Los Angeles has the most unhoused people and for many, many years was using the most punitive criminalization measures.

And then if you put the institutional racism on top of that, Black folks are something like seven or eight times overrepresented in the unhoused community.

[Several police officers and city workers are seen conducting a sweep.]

MAN: They can’t throw my family heirloom away!

PETE WHITE, voiceover: Most people, when they hear the word “sweeps,” they think like sweeping the sidewalks is a great thing. But sweeping an encampment, this entails scores of police. Heavy industrial equipment.

Where else in the world would one use a bulldozer to remove a camping tent?

[Person with megaphone]: People are going to be sitting on the side of the curb, trying to figure out how they’re gonna get the money to buy a stick of deodorant. This is very violent.

You have a man who has a whole mechanic shop out here. And you guys just bulldoze people’s stuff away, like it don’t mean nothing.

[A person carries a ladder away from police.]

He wants his ladder. He wants his ladder, man.

PETE WHITE, voiceover: Once we actually understand the purposes of a sweep, and that purpose is not to help get the individual into housing, then we understand that there’s something really broken with this system.

[pause]

[A man examines the contents of a box outside.]

HARVEY: Want some Narcan? Joanna brought me a whole box again, and it’s good until 2026. That’s good.

I’m not a drug addict. I don’t want to do it. But then again, I can’t turn my back.

That’s one thing I will never do, is turn my back on somebody who needs stuff like this.

I’ve been doing it for the 24, next month will be 25 years that I’ve been living out here.

Now we have to move.

[We see a flier taped to a utility pole with the title “NOTICE MAJOR CLEA” and a date and time.]

I get it that they want to fix this up, and that’s why we have to leave. But we’re not gonna be able to come back.

Shouldn’t have had all this stuff.

They’re gonna fence it. They’re gonna put a fence here so that nobody can come in here to stay.

We are a community. When you see a group of homeless people, that’s community.

[Standing in a tent encampment as people pack belongings into a truck, Harvey hugs a woman.]

HARVEY: Thank you for coming.

HARVEY, voiceover: They’re all set up near each other, that’s community. But see, they don’t see it that way. They don’t see that we actually can protect each other.

I became homeless after I lost my house due to a fire.

I was on the freeway, I was moving in, I was coming over here to LA.

All of a sudden, I started getting tunnel vision.

And I went to the doctor and I was shaking, really shaking so much that he just stood there looking at me, and he knew that it was the Parkinson’s.

I can feel that it wants to act up. I’m not young anymore, so I really wish I had my own place, that would help me with not only getting off the streets, but it would also help me with my medical problems.

If I start to shake at least it’ll be in private. Not in a tent.

[pause]

[Two women walk across a street. One of them is pulling a wagon full of paper bags.]

SONJA: So we do a lot of outreach at the Grand.

We haven’t done around the building yet, so that’s why we were talking. Because there’s a lot of unhoused people right here.

People get lost. Like when they look at somebody that’s unhoused. They just see this, like, drug-addicted, damaged person.

They don’t ever look at someone like, oh, they have a family.

That’s some down there? Yeah. Down there.

[Sonja and her companion are talking with a man next to a tent.]

MAN: How much is it?

SONJA: It’s free.

MAN: I’ll take it.

SONJA, voiceover: Pretty much most of Los Angeles is a paycheck away from being unhoused.

You could lose your job, lose a spouse, have something maybe traumatic happen and maybe lose your mind for a moment.

It could happen to anybody. I’ve met lawyers. I have a friend who used to be a nurse. It’s the worst feeling in the world to have somebody walk by you like you’re not even there.

[Sonja walks by a broken fence along a street.]

So yeah, we used to stay right here, like along this fence.

So you can tell where mine is, see where the cutout is? That hole right there?

[laughing] We had that hole!

I lived right there for the majority of the time that I was unhoused. Close to seven years.

Every Tuesday, all of that area would get swept.

It would be like half the police for was out there. Like are you kidding me?

The minute eight o’clock would hit, they would throw up the tape. And if you didn’t have one thing, you lost it. They didn’t care. They would throw your s**t away, and not even think twice about it.

[Images of black & white photos.]

I had a lot of personal family photos. Things from my dad who passed away, and they got swept.

It was like super demeaning, you know?

And, you know, I sat in that space for a really long time when I was unhoused.

Like I was undeserving of doing better.

PETE WHITE: So of course the effects of criminalization on houseless people, it’s a horrible disruption.

GENERAL DOGON, Human Rights Organizer, LACAN: They start off. They don’t come and just unzip your tent and walk in. No. They start off with a razor blade. And slice your tent down the middle, killing your tent right there. It ain’t no good no more.

GISELLE HARRELL, Resident and Organizer, Aetna Street: So they’re there to specifically take our personal belongings and throw it away.

So I’m like, it’s not a cleanup.

GENERAL: They took this woman’s urn of her mother’s ashes. And I mean, the screams that woman would yell, was like somebody was taking her baby away from her.

[A man with a face mask carries a meowing kitten.]

RONALD PAUL HAMS, Resident and Organizer, Aetna Street: Just last week, I lost everything from personal belongings, to electronic devices… I.D., everything, so you know, I have to start over, pretty much all over again.

GISELLE: And it’s a traumatic event. Like every week. Every week we have to go through this.

RONALD: I went overseas and I fought for my country and watched a couple people die for theirs.

I can’t even walk on it or live on it or lay on it?

That’s a slap in the face.

SONJA: When you’re on the street, you feel like completely isolated. Even though you’re around a billion people. You’re, like, alone in your head.

Makes it very hard to get your feet back on the ground, and that f***s with your head after a while.

I don’t know. It’s like really, really cruel.

[pause]

[Text]

part two

[Michelle, from part one, walks toward a bag checkpoint.]

MICHELLE: I got lucky because I network and network and network, and I was the lucky one that they had one space for a woman.

And I got a Chinatown container home.

The sadness from not having a place went away.

And then I became sadder because I’m by myself.

[Michelle takes a seat on a city train.]

MICHELLE: I do this every day.

Because I could be in my little room, with my heater and air conditioning.

But what’s the point of that, if my heart is right here with my family and friends?

They should have took us all together.

[Michelle walks into a tent encampment.]

WOMAN, with dog: She just ate a whole bowl of food!

MICHELLE: It’s my son, my boyfriend, my friend, my daughter-in-law. They’re all out here still. I’m not leaving them like that.

I’m the mom.

Since we can’t afford to buy clothes all the time. So we sew everybody’s holes!

Like hoodies, jackets…

What would I like?

I would like everybody to get off the streets, into some kind of housing, and not have to be like this.

[Michelle is back on the city train.]

MICHELLE: It’s not right.

So I go home, I come back. I go home…

I’m the mom.

I have to come back.

[pause]

[Harvey, from part one, is walking along the street.]

HARVEY: What are you guys up to?

They’re chasing us out of here.

They’re going to take us on a bus. Three of us, with our stuff to the motel.

I couldn’t sleep last night.

I was thinking about what’s happening today because I have to get rid of stuff and you can only take so much.

We’ll give you 60 gallon bags, two.

Whatever you fit in that, is what you can take to the room.

BECKY DENNISON, voiceover: Emergency housing is really, really expensive. The one that’s the most unsustainable is the use of motel rooms.

Paying $140, $180 per night. We’re talking thousands of dollars per person to live in these motel rooms. And it is absolutely not sustainable.

It comes at the expense of people’s lives and at the expense of permanent housing options that could have been invested in with that same amount of funding.

So if it really was, you know, 60, 90 days and then they’d be moving on, you know, that could work.

But that’s not the way it happens, because we have no place for people to go.

[Harvey smokes a cigarette outside a motel at night.]

HARVEY: It feels isolated.

I feel like I’m very isolated here because, you know, the rules are that you can’t go visit your friends. The ones that came with me over here, that I convinced to come over here.

They even make you sign a form saying that you promised that you wouldn’t be going to room to room.

[interviewer]: And they’re in the same hotel right?

HARVEY: Yeah, they’re above me.

To me it’s more a prison.

It’s more of a prison. But with a revolving door that we can come out here and get fresh air or whatever.

I wish I could get somehow the right help.

That would help me find a place cheap enough for me to afford, that I’ll be able to live there at peace on a permanent basis.

[pause]

[People are holding signs and chanting outside.]

[person with megaphone]: Housing is a human right!

[crowd]: Fight! Fight! Fight!

SONJA, voiceover: I could never do the work I do if I wasn’t in housing.

[Sonja walks a dog into a house.]

I was on the street for about six plus years, and I finally got my housing voucher.

I have a great landlord, who has already worked with Section 8, and helped me get in here.

They take 30% of whatever income you get. So if you get no income, then you don’t pay anything.

When I first moved in, I wasn’t full time working yet.

My rent was $10 a month.

And now I’m paying like $1200, and they pay the difference.

[We see the inside of Sonja’s full walk-in closet.]

I’ve always had a ‘shoe thing.’ But now I have a bigger ‘shoe thing.’

When I got into my own place, it was like, ‘Oh my God I’m me again.’

You know, it was huge.

I got offered the job like two months into getting my housing.

[Framed photos are hanging on the wall.]

Now being inside, every time I see my mom she sends a box of pictures.

And gives me a lot of old photos, you know, those black and white ones of family.

And so I decided to litter my walls with them.

When I first came here, I secluded for the longest time because I was just, like, soaking it all up.

It was huge, to like, not have to worry about your stuff getting stolen. Or if you can go to sleep or not, if you’re going to be safe.

[Sonja swipes down a phone screen.]

My calendar is nuts. That’s what my calendar looks like.

It just made me fight even harder to, like, keep my job and make sure that I don’t lose it.

BECKY DENNISON: Permanent housing. It is the only solution to homelessness, both for individuals and for our region.

PETE WHITE: The solutions are right at our fingertips, but the political will does not exist.

BECKY: Because it’s about the appearance versus the solution.

PETE: If we had real budget hawks you would say: Those strategies that push people everywhere are actually more expensive.

BECKY: Every piece of research will show you that permanent supportive housing is really, really effective.

PETE: The only way that this is fixed is that we’re building housing in every community.

BECKY: That’s the investment that any industrialized, wealthy country besides the United States has made.

And we need to make it.

[Sonja stands at a podium in front of people.]

SONJA: Hi, my name is Sonja Verdugo, and I’m an organizer.

SONJA, voiceover: My work means everything to me.

I could never maintain my job right now, if I was on the street. There’s no way.

It’s probably the most fulfilling thing I’ve ever done.

I feel like I’m part of the push to make the difference somewhere down the road.

It’s gotta start somewhere.

And I think the people in LA are tired.

Of seeing how things are.

And they’re ready to fight.

[pause]

[Text]

In June 2024, the US Supreme Court issued a ruling that further enables cities to use criminalization as their primary response to houselessness, even when people have no place else to go.

Research and experience point to a better approach.

Creating permanent, affordable housing, with supportive services for those who need it, is the proven way to end houselessness.

Tell your representatives to end criminalization and prioritize housing as the solution.

Arrests and citations as the direct mode of criminalization have decreased substantially over the past several years in Los Angeles. But authorities use the threat of arrest to support the relentless taking and destruction of unhoused people’s property through sanitation “sweeps” and people’s removal from certain public spaces. Criminalization has simply taken a different primary form, though punitive criminal enforcement always looms.

Criminalization responds in destructive and ineffective ways to legitimate concerns about the impact of houselessness on individuals and their communities. Rather than improving conditions and leading towards a solution, criminalization diverts vast public resources into moving people from one place to another without addressing the underlying problem.

In contrast to criminalization, housing solves houselessness. Policies that have proven effective include the development of affordable housing—with services for those who need them—preserving existing tenancies and providing government subsidies that help people maintain their housing.

This report takes an in-depth look at houselessness in Los Angeles and at city policies towards unhoused people in recent years, with reference to historical practices. It looks at criminalization enforced by police and the sanitation department and explores how homeless services agencies and the interim housing and shelter systems sometimes support and cover for that criminalization.

Houselessness in Los Angeles

This map shows where visibly unhoused people live in Los Angeles, based on showing police enforcement actions, Sanitation department sweeps and services provided by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority

Unhoused in Los Angeles

Encounters with the Los Angeles Police Department, Sanitation Department, and Homeless Services Authority

July 1, 2020 – April 22, 2022

5 mi

The report features the perspectives of people with lived experience on the streets who have directly experienced criminalization in all its forms. Human Rights Watch spoke to over 100 unhoused or formerly unhoused people, whose stories and insights inform every aspect of this report. The report features analysis of data obtained from various city agencies, including the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), Los Angeles Department of Sanitation (LASAN), Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA), and the Mayor’s office, that exposes the extent and futility of policies of criminalization.

The report looks at the underlying causes of Los Angeles’ large scale houselessness, primarily the lack of affordable housing. It explains how racist policies over the decades have created a houselessness crisis in the Black community. The report also discusses the proven effectiveness of preserving and providing housing as a solution to houselessness, including examples of people who faced criminalization on the streets and whose lives have dramatically improved once housed. Finally, the report makes recommendations for policies that end criminalization and that move towards solving the crisis and realizing the international human right to housing in Los Angeles.

We use the terms “houseless” and “houselessness” in this report in place of “homeless” and “homelessness” because they are more accurate, and because they more clearly direct attention to what is needed to solve the underlying problem: housing. Calling a person “homeless” implies they do not belong and they should be removed from sight, while calling a person “unhoused” recognizes they have a right to exist in their community and need their human right to housing to be upheld.

Key Findings

- Over 75,000 people are without housing in the county of Los Angeles, including over 46,000 in the city of Los Angeles, which is, according to the official one-day “Point in Time” estimates for 2023, a 10 percent increase from the previous year. While only 1.1 percent of the overall US population, Los Angeles is home to 7.1 percent of the nation’s unhoused. Most unhoused people in Los Angeles live on the streets, in tents, or in vehicles rather than shelters or interim housing.

- On average, over six unhoused people die every day in Los Angeles County.

- Houselessness is caused by a lack of available affordable housing for people with little wealth and low income. Housing costs have increased dramatically in recent years, while working-class wages have stagnated. Over half a million renters in Los Angeles do not have access to affordable housing. The treatment of housing as a commodity, rather than as a right, results in this scarcity.

- Almost 60 percent of renters and 38 percent of homeowners (over 720,000 households) in Los Angeles are “cost-burdened,” meaning they pay over 30 percent of their income for housing, and over half of those are severely cost burdened, paying over 50 percent, while 270,000 Los Angeles households are overcrowded. People in these circumstances are precariously housed and at great risk of becoming unhoused.

- Despite comprising less than 8 percent of the total population, Black people make up one third of Los Angeles’ unhoused people. The odds of a Black person in Los Angeles being unhoused are six times greater than that of a non-Hispanic white person. Historic and current racist structures have made houselessness extreme among Black people in Los Angeles.

- Los Angeles invests heavily in criminalizing unhoused people, which causes human suffering and makes many unhoused people disappear from sight, while doing nothing to solve houselessness. Criminalization is primarily accomplished by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) through arrests, citations, and other coercive actions, and by the Sanitation Department (LASAN) through destruction of encampments and the property of unhoused people.

- Some laws LAPD enforces are written to specifically target unhoused people, like LA Municipal Code section 41.18, which forbids people from existing in certain public spaces; other laws, like those banning drinking alcohol in public or regulating activities in parks, though written to apply to anyone, are enforced by LAPD almost exclusively against unhoused people.

- From 2016 through 2022, 38 percent of all LAPD arrests and citations combined were of unhoused people, including nearly 100 percent of all citations and over 42 percent of all misdemeanor arrests.

- LASAN enforces laws against unhoused people by systematically and routinely conducting cleanings or “sweeps” in which they take and destroy property of people living in encampments, including tents, bedding, clothing, medicine, vital papers, family photographs, and other items of personal value.

- The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) provides services to unhoused people and has helped many get into shelter, interim housing, and some into permanent housing. However, LAHSA violates its own “guiding principles” against criminalization by participating in the sweeps. LAHSA provided shelter or housing referrals to any person at only 10 percent of the sweeps and attained shelter or housing for any person at only 3 percent, but their presence at the sweeps lends a veneer of legitimacy to the destruction by allowing officials to claim they are offering services more broadly.

- Interim housing and shelter move people indoors temporarily, but they are not a housing solution, as they lack the qualities needed to meet the right to housing, and rarely lead to placement in permanent housing. Without enough permanent housing, unhoused people can become stuck in shelters and interim housing for extended periods of time, or they return to living on the streets. This cycle is costly and does little to help people out of houselessness. City officials’ emphasis on interim housing and shelter over increasing permanent housing does not end houselessness.

- Affordable permanent housing, including “permanent supportive housing” for those who need it, has proven effective in combating houselessness, can be cost-effective, and dramatically improves people’s lives and communities.

***

Houselessness, Housing, and Hope: The Case of Sonja Verdugo

Sonja Verdugo was married, had a home in the LA neighborhood of Venice and a job in property management.[1] When her husband relapsed into his addiction and left their home, she fell into financial and mental distress. Over the course of a year, she lost her job and then her home, and herself relapsed after many years of sobriety. She lost connection with friends and family. She ended up in a tent and became part of the unhoused community living between City Hall and Chinatown.

While living in that community, she experienced persistent police harassment. Officers would arrive at 5 a.m. with megaphones demanding they take down their tents and hitting the tents with sticks. Verdugo frequently saw police ticketing people for having their tents up or for having their property on the sidewalk. Twice, police ticketed her for having her tent up, including one time when she put it up earlier than allowed because she was sick. She had no money to pay the fines.

LASAN carried out regular “cleanings” or sweeps in her community, for which they would give people a short time to pack up and move all their belongings or have them taken and destroyed. Verdugo saw the LASAN crews take and trash many of her encampment companions’ property. Police always accompanied LASAN on these destructive sweeps, ready to arrest anyone who delayed the process or resisted destruction of their property.

One night, Verdugo stayed at a nearby encampment to avoid a person who had threatened her. The next morning, LASAN arrived early to conduct a sweep at her home location. They threw away her tent, brand new cart, bed, dog bed and dog food. They put her paperwork, personal effects, identification, and family photographs into a trash compactor truck.

In 2020, after six years on the streets with no help or meaningful services from the government, Verdugo and her husband, with whom she had re-united, were offered a temporary room in a hotel through a program called Project Roomkey (PRK). While she was grateful to have a place to stay indoors with a bed and a shower, the hotel had oppressive rules, including curfews and limits on who could visit. Program staff entered the couple’s room without notice, one time while she was sleeping. Staff took her husband’s tools. She saw people getting evicted from the hotel regularly for minor rule violations.

While staying at the hotel, Verdugo constantly asked case managers for help finding permanent housing, but she got almost no response. They tried to move her into a “Tiny Home Village” (THV), but she refused. THVs are gated lots filled with eight-by-eight foot sheds with two beds, desks, and communal bathrooms, that serve as temporary shelter for unhoused people.

Fortunately for Verdugo, activists with Ground Game LA, a mutual aid and advocacy organization that seeks to empower unhoused people, assisted her; Ashley Bennett, a former Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) outreach worker, was especially helpful. In the summer of 2022, Verdugo connected with a landlord who accepted her voucher.

In September 2022, Verdugo moved into her own apartment. “It is amazing to have this place,” she said. The apartment is comfortable; she feels safe. She can lock her doors. She no longer worries about having her property stolen or destroyed. Her apartment has air conditioning, a television, a kitchen, and a shower.

Her husband died shortly after they moved into the apartment, but she is grateful he did not have to die on the streets. Having a home allowed her to be physically and emotionally present as he was dying and to properly mourn. It allowed her to help her stepson cope with the loss of his father. Having a home has allowed her to re-connect with friends and family in ways that were not possible while living on the streets. She has made friends among the people in her building and her neighborhood.

Grateful for the help she received, Verdugo now works for Ground Game helping other unhoused people navigate the system and advocate for themselves.

“My success is not normal. I had so much luck. I had Ashley and others help me. So many people don’t have advocates. So many are isolated.”

Verdugo has a wall in her new apartment covered with photographs of her family that LASAN workers will not be able to take and destroy.

***

Houselessness in Los Angeles

According to the official counts, in 2023 there were over 75,000 unhoused people in Los Angeles County, including over 46,000 in the City of Los Angeles, the largest unhoused population among US metropolitan areas and a dramatic increase from just a few years earlier. Over two-thirds of those were not in shelters or interim housing, but, instead, were living on sidewalks, in parks, on median strips and the sides of freeways, or in their cars, vans, and recreational vehicles. This official number, produced by volunteers one night in January as part of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority’s (LAHSA) annual “Point in Time” count, may be a significant underestimate. It misses the many people living in motels, on friends or family members’ couches, in hospitals and jails or otherwise out of sight at the time of the count.

Unhoused Population Growing

Line chart with 2 lines.View as data table, Unhoused Population Growing

The chart has 1 X axis displaying values. Data ranges from 2016 to 2023.

The chart has 1 Y axis displaying values. Data ranges from 28464 to 71320.

End of interactive chart.

The number of visibly unhoused people is just the most obvious manifestation of the housing crisis facing Los Angeles. Hundreds of thousands of residents are precariously housed, one medical bill or missed paycheck away from losing their homes and landing on the streets. Over 720,000 households in Los Angeles, including renters and homeowners, are “cost-burdened,” meaning they pay over 30 percent of their income for housing; over a quarter of all renter households are “severely cost-burdened,” paying more than half of their income for rent. In Los Angeles, 270,000 people live in overcrowded homes, 80,000 in homes defined as “severely overcrowded.” These indicators of housing precarity are the highest in the US. People in these situations can flow in and out of houselessness easily.

Renting and Ownership in Los Angeles

% of households that rent their homes, 2022

Legend

- 0-20%

- 20-40%

- 40-60%

- 60-80%

- > 80%

Source: Human Rights Watch Analysis of US Census Bureau data, American Community Survey 5-year data (2018-2022)Data: Renting and Ownership in Los Angeles

Rent Burden in Los Angeles

% of renters who are rent burdened, 2022

Legend

- 0-20%

- 20-40%

- 40-60%

- 60-80%

- > 80%

Source: Human Rights Watch Analysis of US Census Bureau data, American Community Survey 5-year data (2018-2022)Data: Rent Burden in Los Angeles

The unhoused population includes a growing number of older people, women, families, young adults often leaving foster care, and people with disabilities, including those with high support requirements because of their mental health conditions. While making up only about 8 percent of the overall population, Black people are more than a third of Los Angeles’ unhoused. The Latinx unhoused numbers are growing.

Living on the streets has become increasingly deadly, as disease; drugs, especially opioids and methamphetamine; and the stress and ravages of living exposed take their toll. In 2021, over 6 unhoused people died on average every day in the county of Los Angeles, up from 1.7 in 2014.

The Causes of Houselessness

The lack of available affordable housing is the primary cause of houselessness. If there is not enough housing available and accessible for everyone regardless of their income and wealth, then some people will be forced onto the streets. People with social risks that limit their ability to compete for this scarce resource are the ones who end up unhoused. Those most at risk include people with different types of disabilities or mental health conditions, people subject to racial discrimination and systemic racism, survivors of domestic violence, people with criminal records, people living with addictions, people without family support, especially youth and older people, unemployed people and people with low incomes. Wages and social security payments for working class people in Los Angeles and throughout California have not kept up with housing costs.

Los Angeles and Other Californian Cities Lead US in Change in House Prices

Line chart with 47 lines.

Percent change in typical home value since 2000 in 50 largest US cities (California cities in blue)View as data table, Los Angeles and Other Californian Cities Lead US in Change in House Prices

The chart has 1 X axis displaying Time. Data ranges from 2000-01-31 00:00:00 to 2024-01-31 00:00:00.

The chart has 1 Y axis displaying values. Data ranges from -61.90704807 to 346.1953304.

End of interactive chart.

Without effective government action, market-based development that treats housing as an investment and means of accumulating wealth rather than as a right often results in outcomes harmful to rights. The cost of building in Los Angeles is extremely high, and it rarely makes economic sense for profit-driven actors to create affordable housing without some government incentives or interventions. Studies indicate that 500,000 people in Los Angeles lack access to affordable housing. Housing construction is occurring, but it is concentrated at the high end of the market.

Government action and inaction have compounded the failure and inability of market forces to ensure realization of the right to housing, increasing houselessness. Austerity policies, including dramatic cuts to social safety nets over the past several decades, abandonment of funding for public housing, and removal of regulations that favored affordable housing development and preservation, have contributed to the crisis. Instead of directly funding housing for people living in poverty, the government has created programs to financially incentivize investors to develop affordable housing on a relatively short-term basis, creating highly inefficient mechanisms for building this housing and leaving hundreds of thousands of units across the country exposed to expiring affordability guarantees.

Government policies that, either explicitly or implicitly, enforce racial boundaries and remove wealth from or deny wealth to Black communities have led to disproportionately high rates of houselessness among Black people in Los Angeles and across the US, a manifestation of white supremacy. Redlining mandated by federal lending programs, racially biased zoning rules, freeway construction through Black communities, many urban renewal projects, and systemic discrimination and disinvestment in education, health care, and community infrastructure have all served, alongside discrimination by private actors through restrictive covenants and real estate marketing tactics, to increase Black houselessness. Policing and the “wars” on drugs and crime that have focused on Black communities have added to the problem.

Criminalization

While there are ongoing efforts at all levels of government to address the lack of housing, these efforts have rarely been resourced at the levels needed to meet the problem. They do not seriously grapple with the market forces and longstanding discriminatory policies that underlie systemic houselessness. Instead, the prevalent response by government, often prompted by demands from some housed people and business investors to simply remove unhoused people, has been criminalization.

Criminalization is enforced by a broad variety of government officials. In Los Angeles today, police and sanitation workers—whose cleaning or clearance operations are often accompanied by police and always backed by threat of citation or arrest—are the lead agents of criminalization. Homeless services outreach workers, many of whom genuinely seek to assist unhoused people, too often are pressed into participating in criminalization by facilitating the destruction of encampments and providing a veneer of compassionate treatment, in turn providing cover for these harmful actions. The provision of shelter, through barracks-like congregate shelters, “tiny homes,” more modern shelters that allow some privacy, temporary hotel rooms, and sanctioned camping in gated lots, provide some respite from the streets for a few people, but also allow city leaders to claim legal and moral justification for removing people from public view.

Traditional criminalization through arrests and citations

Enforcement of laws, especially minor code violations, through arrest and citation has been the traditional mode of controlling and removing poor people dating back to vagrancy laws that facilitated enslavement of Native Americans in California, “sundown towns” where Black people were forbidden from being seen in public after dark, and Depression-era laws against migrants living in poverty from other states.

Like scores of cities across the US, Los Angeles enforces laws that explicitly target the existence of unhoused people in public spaces. Los Angeles Municipal Code (LAMC) section 41.18 forbids sitting, lying down, or sleeping on city sidewalks; LAMC section 56.11 forbids keeping property in public places. Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) enforces these laws exclusively against unhoused people. Court rulings over the years have modestly limited the reach and punitiveness of these laws, but the city council has responded by modifying them in ways that retain law enforcement’s ability to drive unhoused people from public view.

Like scores of cities across the US, Los Angeles enforces laws that specifically target the existence of unhoused people in public spaces. Los Angeles Municipal Code section 41.18 forbids sitting, lying down, or sleeping in designated public spaces throughout the city.

10 ft within any driveway

On bike path

Within 2 ft of any fire hydrant.

Within 500 ft within any freeway onramp, overpass, underpass, tunnel, bridge, etc.

Within 500 ft within any park or library

Within 500 ft within any school or daycare center

Within 1000 ft within any unhoused shelter or homeless services center

This expansive patchwork of forbidden zones leaves unhoused people with few options for where they can legally exist.

Los Angeles Municipal Code section LAMC section 56.11 forbids keeping property in public places.

The Los Angeles Police Department enforces these laws exclusively against unhoused people.

LAPD also enforces laws that do not explicitly apply to houselessness against unhoused people in ways that directly target them for their existence in public. Human Rights Watch analysis of LAPD data from 2016 through 2022 revealed that even though unhoused people account for less than 1 percent of the overall population of the city, 38 percent of all arrests in Los Angeles were of people identified as unhoused, including over 99 percent of all infraction arrests and citations, and over 42 percent of all misdemeanors.

Rates of citations and arrests by housing status (2016-2022)

Felony arrests

7 housed 221 unhoused

per 1,000 people

Arrests ending with a jail booking

14 housed 378 unhoused

per 1,000 people

Misdemeanor arrests

7 housed 640 unhoused

per 1,000 people

Infractions (e.g. citations)

<1 housed 227 unhoused

per 1,000 people

All infractions (e.g. citations) and arrests

14 housed 1,002 unhoused

per 1,000 people

The most common arrest charges are drinking in public or possessing an open alcohol container, accounting for over 21 percent of arrests of unhoused people. According to LAPD data, every one of the over 50,000 arrests made in Los Angeles in those years on such charges was of a person identified as unhoused. Unhoused people account for all people arrested for violating park regulations and for vending; they account for 99 percent of littering citations, over 90 percent of liquor law and gambling citations, over three-quarters of loitering and drug paraphernalia arrests, over half of trespassing and sex work arrests. These offenses nominally apply to all people, but the LAPD uses them against those living on the streets. While police arrest unhoused people at higher rates for more serious offenses, including homicide and rape, they are much more likely to be victims of such serious crimes than perpetrators. Most arrests of unhoused people are for lower-level offenses.

In the mid-2000s, LAPD implemented a program called Safer Cities Initiative (SCI), in which they saturated Skid Row—a predominantly Black community with the highest concentration of unhoused people in Los Angeles and home to low-cost housing and massive congregate shelters—with large numbers of police officers tasked with systematically ticketing unhoused people. SCI resulted in massive numbers of arrests and tickets for people trying to survive on the streets, while its impact on crime was negligible—crime went down in Skid Row during that period at the same rate it went down in other parts of the area not subject to such intensive enforcement. In 2016, Mayor Eric Garcetti discontinued SCI, but maintained a similar police presence under a different name.

In 2019, a federal court ruled that cities like Los Angeles could not punish people for existing in public space unless the cities had “adequate shelter” available. By this time, Los Angeles police were reducing their enforcement of laws, such as section 41.18, dramatically. By 2021, they were making very few arrests, though since 2022, enforcement has begun to increase again.

Even as direct enforcement has slowed in recent years, police continue to have coercive encounters with unhoused people that do not always result in arrests. They stop and search people and order them to move from certain locations. Incidents of force by police against unhoused people remain steady despite reduced arrest numbers. The rate of use-of-force incidents per arrest against unhoused people tripled from 2016 to 2020, and the percentage of all use-of-force incidents that involved unhoused people went up from 25 to 35 percent.

The return of institutionalization

With court-mandated limitations on enforcement of laws like section 41.18, local and state jurisdictions are building up a legal and physical infrastructure to force unhoused people into mental health treatment, eventually including detention and forced medication. In 2022, the California legislature passed the CARE Act, which set up a court process to require people to submit to treatment plans, diverting resources away from voluntary care while pushing people into shelters—without resourcing permanent housing with supportive services (PSH). People who fail to comply with court-ordered treatment can be fast-tracked to conservatorships, a legal status that allows the government to appoint another person or entity to make decisions for a person, including holding them locked in facilities against their will, forcing them to take medications, and controlling other important life decisions.

The following year, at the urging of California Governor Gavin Newsom and the mayors of California’s big cities, the legislature passed SB 43, vastly expanding the reach of conservatorship. They also promoted a bond measure that voters narrowly approved in 2024 that allocates over $6.3 billion to build some permanent supportive housing, but primarily locked psychiatric facilities for involuntary holds. These new facilities will be used, in some part, to detain unhoused people subject to court-ordered treatment.

The proponents of these initiatives to expand forced treatment have stated clearly that they are intended to be used to get unhoused people into treatment. However, forced treatment can be deeply traumatizing, is not as effective as voluntary treatment, and does not address the key underlying drivers of houselessness. These initiatives do not help expand voluntary care, which is already difficult to access.

Sanitation sweeps destroy unhoused communities and harm people

In recent years, city policy has shifted away from arrests and citations and instead emphasized sanitation sweeps. This approach to enforcement has become the primary tool for making unhoused people disappear from public view. Unlike citations that require a court process, the sweeps punish people immediately, on the spot.

LASAN functions alongside LAPD as a primary agent of criminalization. The agency systematically and repeatedly conducts abusive sweeps of unhoused communities, enforcing section 56.11 and other laws by taking property belonging to unhoused people and destroying it.

Unhoused people report that LASAN repeatedly destroys their property, including tents, bedding, chairs, clothing, papers, food, personal keepsakes, money, and medication. As part of the city-wide CARE+ program that targets encampments for “comprehensive cleanings,” LASAN workers give people a short time to pack their homes before they begin to clear unhoused communities. Sometimes they provide notice of these sweeps, but often the notice is not specific about exactly when and where, and sometimes there is no notice at all. Other times, they give notice of a sweep and do not show up. The inconsistency in notifications results in people losing property that they might have saved.

Court rulings have affirmed the rights of unhoused people to keep property, but LASAN has used loopholes that allow them to discard items they determine to be “contaminated” to systematically destroy property. Section 56.11 also authorizes them to take “excess” property from unhoused people, defined as anything that does not fit in a 60-gallon bag.

LASAN conducts “spot cleanings,” in which they simply removed trash without taking property and destroying tents. Unhoused residents generally appreciate these types of cleanings. They also conduct “comprehensive” cleanings or “sweeps” in which they confiscate and destroy property. LAPD officers are nearly always present or easily accessible, serving as a threat of arrest for people who disobey LASAN workers and attempt to salvage their property.

With only a few exceptions, the city does not provide trash cans, dumpsters, toilets, or hand-washing stations to encampments, and so garbage accumulates, as people live in unsanitary conditions.

Across the City of Los Angeles from April 2020 through October 2022, LASAN conducted 25,000 major cleanings, each removing over 100 pounds of material and averaging 1.3 million pounds removed each month. Despite a legal requirement to bag and store uncontaminated property, rather than destroying it, LASAN rarely does so, averaging only 72 bags stored a month throughout the city.

The repeated cleanings, even non-destructive ones, expose the futility of policy responses that prioritize criminalization and fail to provide housing: people remain unhoused, possessions and garbage inevitably accumulate again on the street despite the millions of dollars spent throwing them away. The lasting impact is severe trauma for those who must rush to pack-up and move their makeshift homes and end up losing their valued property repeatedly.

LASAN targets the areas repeatedly over time. The maps below show pounds of material, including the personal possessions, disposed of by LASAN during encampment sweeps.

Venice Beach: Pounds of material, including personal possessions of unhoused people, removed by LASAN during encampment sweeps.Hollywood: Pounds of material, including personal possessions of unhoused people, removed by LASAN during encampment sweeps.Skid Row: Pounds of material, including personal possessions of unhoused people, removed by LASAN during encampment sweeps.

Homeless service provision has served criminalization

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) is a joint city and county agency responsible for coordinating services to unhoused people, including helping with re-housing in both permanent housing and temporary shelter. In addition to its own outreach structure, LAHSA oversees numerous independent organizations that provide services. LAHSA has had some success housing people and placing them in shelters, though their claims do not match Human Rights Watch analysis of their data. Despite their success, many more people flow into houselessness than they can help.

LAHSA’s effectiveness is limited by the shortage of permanent housing. Despite increased funding for shelter and housing, there simply is not enough to meet the crisis. Given the scarce resource, LAHSA has a system for prioritizing those with the highest risk, called the Coordinated Entry System (CES). This program has substantial flaws, including an acknowledged racial bias which LAHSA representatives say they are attempting to remove.

LAHSA service provision is most effective when they conduct “proactive” outreach—seeking out unhoused people, building trust over time, and providing resources voluntarily. Unfortunately, LAHSA has given in to demands by city officials, particularly in City Council offices, to actively participate in destructive sanitation sweeps, upending the process of trust and rapport building.

Rather than use a prioritization system based on the individual’s need, LAHSA has allowed the City Council offices to direct services to the most visible encampments—those that are the subject of public complaints and are important to elected officials. City Council staff often tell LAHSA to which encampments they must direct resources, especially access to shelter. While people in these locations may gain the benefit of getting indoors, often only after having to surrender their personal property and submit to jail-like rules, others from less visible places who may desperately and uniquely need to move indoors remain outside.

Responding to political pressure, LAHSA leadership has required outreach workers to participate in the destructive CARE+ sweeps. While they can provide some services, their role largely has been to advise people that they need to move and what they must do to comply with sections 56.11 and 41.18. Their presence allows city officials to claim that the sweeps have a services component and that encampment clearances result in people getting housed, despite the fact that relatively few people do get housing.

At some of the bigger or more high-profile encampment clearances in recent years, like the ones at Echo Park Lake, MacArthur Park, Venice Boardwalk, or Downtown Main Street, LAHSA has been present offering shelter and hotel rooms; at the lesser-known locations all around the city they may be present, but they have little to offer beyond bottles of water and instructions to cooperate with the destruction of people’s property.

Unhoused in Los Angeles

Click on any area throughout the city to see data on LAPD arrests of unhoused people, LASAN sweeps and cleanings, and services offered to unhoused people by LAHSA between July 1, 2020 and April 22, 2022

Source: Human Rights Watch analysis of LAPD, LASAN and LAHSA data, on file with Human Rights Watch. Data on housing attainment only includes those who are marked as having attained housing in the LAHSA data. It is possible that the LAHSA data does not contain information on all individuals who have attained housing.

Without permanent housing, interim shelter does not solve houselessness and is used to justify criminalization

Shelter and interim housing can have great value in getting people off the streets and into safer situations. However, shelter and interim housing do not meet the standards for housing spelled out by international human rights law. As Los Angeles lacks an adequate stock of permanent housing, people can remain in these deficient living situations for extended periods of time, or they leave and return to houselessness.

City officials use the existence of shelter and interim housing to justify, both legally and morally, implementation of criminalization policies—they can say that they offered “housing” before destroying an encampment and scattering its residents. They can move a certain number of people indoors, while the vast majority remain on the streets facing increasing enforcement of laws that punish their existence in public.

According to international human rights law, permanent housing means a place to live that is not temporary or time limited and that meets standards of habitability, affordability, accessibility, and security of tenure. The services agency and city officials have very little permanent housing to offer; instead, they offer various forms of shelter, including hotel rooms, primarily through the Project Roomkey (PRK) and Inside Safe programs, congregate shelters, A Bridge Home (ABH) shelters, Tiny Home Villages, and Safe Camping, which provide space in gated lots for people to set up tents. Despite this variety of options, there is not nearly enough shelter for everyone living on the streets. PRK, for example, peaked in August 2020, sheltering just over 4,472 people; one year later the program only served 1,392 people and continued to decline.

While these shelter situations allow some people to get off the streets and many who stay in them are grateful, they are temporary solutions, at best. Living conditions range from comfortable to uninhabitable. Many people refuse to enter congregate and other shelters due to lack of privacy, safety concerns, and unsanitary conditions. All the shelter options have degrading and even draconian rules that may include curfews, searches upon return to one’s room, prohibitions on guests, pets, and even partners or spouses, limits on keeping property, and other restrictions. Many unhoused people compare the conditions to being incarcerated.

The shelters have not led consistently to placements in permanent housing. City and county officials tasked with optimizing a system to rehouse people calculate that a successful system must have five permanent units for every one interim or shelter bed. This ratio allows a steady flow of people from the streets to shelter to housing. Los Angeles has far fewer permanent units than needed, and so the system stalls. Without that flow, people either stagnate in the shelters or they leave. When people leave, returning to the streets, new shelter beds are available, but these extremely expensive programs have not made a dent in the unhoused population.

The shelter or interim housing system has facilitated criminalization. The ABH shelters are surrounded by Special Enforcement and Cleaning Zones (SECZ) in which city policy empowers and housed neighbors expect police to enforce laws against unhoused people and where, more prominently, LASAN conducts repeated destructive sweeps. Human Rights Watch analysis of LAHSA data shows evidence supporting claims that in advance of high-profile encampment sweeps, city officials held hotel rooms empty so that they could show the public that they were placing people from those encampments into rooms rather than simply scattering them to other unsheltered situations. In doing so, they underutilized the rooms and left others, from less visible locations, unsheltered.

Officials often justify the cruelty of encampment destruction by claiming they have successfully “housed” people, when at most they have moved people into shelter options, often taking rooms from more vulnerable people who need to be indoors. Sweeps of lower profile encampments typically do not even result in shelter placements, especially as shelter beds are also scarce.

Despite the grave need to develop more permanent housing to effectively move people out of houselessness, policymakers in Los Angeles have trended towards prioritizing interim shelter over permanent housing, directing scarce resources away from the long-term solution.

Inside Safe and the Bass Administration Approach to Houselessness

The mayor of Los Angeles, Karen Bass, has publicly made houselessness her administration’s top priority and has promised a new approach that will solve the problem. She has issued orders declaring a “state of emergency,” and required city agencies to speed up the process of approving affordable housing developments.

Housing developments funded through Proposition HHH, passed by voters in 2016, should become ready for occupancy and allow for more permanent placements, though they are a finite resource. Measure ULA, a voter-approved tax on property sales over $5 million earmarked for permanent housing development and tenant protections, will give the mayor additional funds. She has promised to access federal and state resources.

However, despite her public pronouncements Bass has been prioritizing interim housing and shelter over permanent housing and has allowed criminalization to continue unabated. She has allocated $250 million to her signature program, Inside Safe, which mobilizes LASAN and police to destroy encampments permanently, while moving their residents to hotel rooms on a temporary basis. As with PRK, many people are grateful to get indoors, while others resent being forced into rooms that often have severe habitability problems. Officials have required people to surrender much of their property for destruction as a condition of accepting the hotel rooms. People who have declined to move into hotel rooms face destruction of their property and banishment from locations where they had been living. While touted as a pathway to housing, very few people have left the hotels for permanent situations—more have returned to houselessness.

As of September 2023, there were only about 1,100 Inside Safe rooms available, requiring choices about who would be placed in them. The Bass administration selection process has prioritized publicly visible encampments as opposed to setting aside rooms for people with the most need. This prioritization appears to be driven by City Council office preferences and complaints from housed neighbors, rather than helping the most vulnerable.

Housing Solves Houselessness

Housing people solves houselessness. Helping people retain their homes prevents inflows to houselessness. Developing and preserving affordable housing allows more people to stay housed and reduces housing precarity that leads to houselessness. Upholding and increasing tenants’ rights empowers them to maintain their housed status. Housing is different from temporary shelter or even “interim housing.”

Most unhoused people simply need a permanent, affordable, habitable place to live. Some people with disabilities need housing with a spectrum of support services attached, often called “permanent supportive housing” or PSH. Ample experience shows that providing PSH to “chronically” unhoused people—those with disabilities who have been on the streets for over a year—is extremely effective, with one-year retention rates around 90 percent. The Housing First model, in which people are housed voluntarily and without requirements of sobriety or treatment compliance, has been successful in a wide variety of jurisdictions in allowing people to stabilize and remain housed.

There are a variety of approaches to housing, each with relative benefits and drawbacks. Prominently, the federal government provides vouchers under the Section 8 program that allows tenants to pay 30 percent of their income in rent while the government pays the rest. There are not nearly enough vouchers for all who qualify for them; people with vouchers often cannot find places to stay due to discrimination and bureaucratic barriers; vouchers do not increase the overall number of affordable units. But, for those who do find housing with them, vouchers have greatly improved their lives.

Non-profit housing developers produce and manage permanent housing and PSH, despite a highly inefficient financing system and an overall shortage of funds. Advocates are calling for Los Angeles officials to convert hotels and unused commercial buildings to affordable housing, and to create land trusts that remove properties from the speculative market so that they can provide permanently affordable housing. While public housing, permanently affordable and financed entirely by government, has been demonized and starved of funding in the US, it can be an effective approach to delivering the right to housing.

Compared to criminalization and prioritization of temporary shelter, which do not solve houselessness, providing permanent housing is cost effective over the long-term, including through savings from reduced reliance on emergency services, lower court and jail costs, and reduced direct expenditures for sanitation, temporary shelter, and police interventions. The intangible human benefits of replacing policies grounded in cruelty with policies of care make housing production and preservation an obvious choice.

Human Rights Watch has documented numerous cases of people who were housed successfully after periods of houselessness. The positive change in the life circumstances of each of these people points to a way forward that will benefit unhoused people as well as housed people and will increase the value of communities in Los Angeles.

Relevant International Human Rights Law

International human rights law recognizes the right to adequate housing. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) articulates and international treaties including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) enshrine this right. The US has signed, but not ratified these treaties, creating an obligation not to undermine their purpose and object. Implementing criminalization while neglecting to guarantee housing for all undermines the right.

The right to adequate housing, as defined by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, is not simply the right to shelter, but to housing that, at minimum: 1) has legal security of tenure; 2) has facilities, like water, sanitation, and site drainage, essential for health, security, comfort, and nutrition; 3) is affordable, without compromising other basic needs; 4) is habitable; 5) is accessible, accounting for disabilities and reasonable accommodation; 6) is located in a place accessible to employment, education, health care, and other social facilities; 7) is culturally appropriate.

The US has signed and ratified the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), obligating it to uphold the right to housing in the context of combating racial and ethnic inequity. The long history and current policies of racial discrimination that have led to the prevalence of Black houselessness call for remedial and reparative actions.

Criminalization in all its forms violates the right to life, liberty, and security of person and prohibitions against “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment,” found in International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) also prohibits cruel and degrading treatment. The US has signed and ratified both treaties, obligating it to comply with them. The UN Human Rights Committee has interpreted policies that punish life sustaining activities, like sleeping, as potentially cruel and degrading treatment. The ICCPR protects against arbitrary arrests, including arrests for the status of being unhoused.

As criminalization exposes Black and Brown people disproportionately to arbitrary arrest and cruel treatment, it may violate the ICERD’s mandate to end discriminatory policies and to mitigate racial harms, regardless of discriminatory intent.