Arguing about toy weapons: relax, and stand your ground

Translation: Patrik Stainbrook

Whether during Carnival, the average Nerf phase or at a laser tag event – almost every child will get their hands on a toy weapon at some point. I had problems with it at first, but now I’m pretty relaxed about it.

When I think of carnivals from my childhood, the first thing that comes to mind is a small, dirty silver toy gun. It was pretty heavy, the grip solid and the barrel open. Compared to today’s cowboy revolvers, it looked pretty menacing. New ones are usually made of plastic and the barrel is visibly sealed with a red plug.

Sombo Denver pistol

26

However, I didn’t really care what happened at the front. After all, percussion caps could be clamped in the back and, with a bit of luck, could be made to pop by pulling the trigger. The noise, the flying sparks and the small, sulphurous clouds of smoke in the air are etched in our memories. Alongside our parents, who thought this fascinating toy was dangerous.

I couldn’t understand why. I wasn’t thinking about life and death, nor about fear and threats. Just fun in the moment. And the fact I was able to set off little fireworks as a kid.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/Harry20, CC BY-SA 3.0

Yes, we were reprimanded when we took aim at each other. But even if we did, we were probably just playing tag from a distance. «I got you!» – «No, I had you first!» Innocent times. A long time ago, some decades later, I saw my own child handling a toy gun for the first time. Just as enthusiastic, just as enraptured and, as expected, without a hint of inner conflict. Something I had in spades.

Find your own stance

It all started with a need to protect. I didn’t want to see my kid racing through the neighbourhood Rambo-style, I didn’t want to build up an ammunition depot in their room and I wanted to stick with building blocks forever.

Of course, all these thoughts were wildly exaggerated. But the topic of weapons immediately looms large in people’s minds since it resonates so much more with adults. It marks the beginning of the end of innocence. It’s not the child’s fault, they just immediately have to deal with the irritation that mommy and daddy obviously don’t like this fabulous new toy. Turns out I hadn’t even made my mind up yet. What to do with all my memories? With all the fun I had as a child? What’s okay, and where’s the line of good taste in my eyes?

As soon as I think about it, I realise that my thoughts on the subject are anything but consistent. Why do I see water pistols as completely harmless summer fun, but Nerf guns make me uncomfortable? How can I shoot at turtles with fireballs as Super Mario, but criticise the paintball battle in Splatoon 3? What’s the difference? And why do I have a problem with it, even though toy guns today have to look much less realistic and are no longer as loud as they used to be? It’s hard to explain, but there’s no getting around it: these conflicting feelings need to be discussed.

Being disarmingly honest

I don’t believe in strict bans. Something that fascinates them will sooner or later find its way into a kid’s hands anyway. In that case, it’s better if they have at least a little moral preparation. Basically, I think I’ve observed two things about my behaviour. My reaction is more negative the more a toy resembles real weapons. And to be honest, even if it’s too new for me to associate positive memories with it.

The first point is understandable, the second doesn’t really make sense. A child can understand relatively early on that weapons look threatening and cause suffering in real life. And that’s already a win. Just like when I express my understanding that playing with it is fun. A confession like that and interest in the topic ensure that I don’t block out my kid from what I’m feeling either. That’s vital, only then can a solution be found together.

Source: Shutterstock

The first heated discussion was about Nerf – yes or no? As soon as some classmates had the plastic weapons, the topic got hot, the gun was in high demand and my attitude towards my kid was ultimately this: neither Santa Claus nor the Easter Bunny would become a weapons supplier. If they really wanted one of them, they’d have to buy it with their own money. That eventually came to be, and I tried to refrain from making negative comments and pointing fingers. I even used it regularly and played along.

Setting and enforcing boundaries

Being involved carries the advantage of being able to intervene and regulate things. After all, a shooting game like this is always on the verge of getting out of hand. You have to be clear where the boundaries are. This is a duel. Things should be fair, and clear rules should apply. For example, only aim at people playing and no shooting from close range. If that doesn’t work, the guns will be gone right quick before they’ve even realised they’re not interested in playing with them any more.

Our Nerfs have been gathering dust in some drawer for a few years now. Instead, questions of war and peace are increasingly shifting to the digital realm. When talk on the playground stops being about Pokémon but about headshots, the perspective shifts and hardly any family can maintain their basic pacifist line. In turn, anything associated with physical activity immediately sounds much better.

Source: Shutterstock

Former Nerf sceptics have long since hoisted the white flag, happily sending their children off when the fifth invitation to a laser tag birthday party flutters through the door. Teams shoot at each other with semi-realistic guns under LED lights – then eat cake together in a great atmosphere. Peaceful. In my opinion, with just a little guidance and clear boundaries, children will find a healthy approach to toy weapons – analogue or digital.

The 6-year-old accused of shooting his teacher shouldn’t be punished under the law

Interventions can help violent children — and their parents.

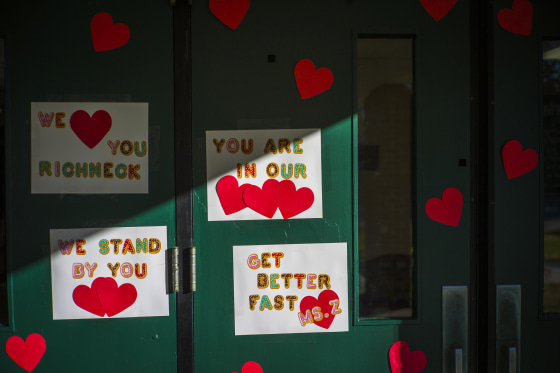

Messages of support for teacher Abby Zwerner grace the front door of Richneck Elementary School in Newport News, Va., on Wednesday. John C. Clark / AP file

According to the police, a 6-year-old boy at Richneck Elementary School in Virginia used a gun legally purchased by his mother to intentionally shoot his teacher on Friday. The event is shocking and unnerving, and, as with other crimes, we instinctively want justice for the victim and a way to ensure the perpetrator doesn’t do further harm.

So it’s easy to see this child as deeply troubled and label him a menace to society. Some of us may want to lock him up and throw away the key. But as a psychologist who researches traumatic stress and treats its survivors, I hope we don’t. Instead, I hope we have compassion and provide mental health intervention for the injured teacher, the classmates who witnessed the shooting, the community that’s reeling from the attack — and also for the child who pulled the trigger. Why? Because, research shows that most children who get intervention early for violent behaviors recover.

The research indicates that “positive and warm relationships,” rather than punishment in the form of reprimands and negative consequences, have the greatest impact.

We can assume the child is no doubt suffering from trauma himself because shooting someone, whether intentional or not, is a devastating experience. That means he needs treatment. Moreover, the typical legal remedies don’t make sense for a person too young to understand the full extent of his actions or what long-term punishment entails.

“Given a 6-year-old child’s lack of cognitive and moral development, it makes little sense to pursue aggressive criminal or juvenile justice prosecution of the child,” said Dean Kilpatrick, a professor at Medical University of South Carolina and the director of the National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center. “He does not have the capacity to be legally responsible for this act.”

Indeed, moral development is incomplete in young children. There are different theories as to when humans develop the ability to tell right from wrong, but psychologists generally believe a core understanding of right and wrong happens no earlier than at 9 years of age. Damion Grasso, a psychologist and associate professor at the University of Connecticut, also noted that often, “young children, especially those exposed to violence, can imitate violent behaviors without fully comprehending the ramifications of their actions.”

The good news, he said, is that this means that “there’s a lot of ‘catch-up’ that can happen with proper nurturance and caregiving.” Since imitation is part of how children explore the world, good modeling provided by parents, teachers, community leaders and even peers means they can absorb those behaviors as well.

Teacher shot by 6-year-old student hailed as a hero

Patricia Kerig, a professor at the University of Utah and a leading expert on recovery and resilience in youth, pointed to a large body of research demonstrating the short-term effectiveness of interventions for both conduct disorder — a psychiatric condition in individuals under 18 who engage in a habitual pattern of aggression toward people and animals, destruction of property, deceitfulness or theft and serious rule violations — as well as “what might be thought of as ‘garden variety’ aggressive behavior — bullying, getting in fights on the playground and reactively aggressing against peers.”

Early interventions for children can include preschool intellectual enrichment and skills training that provide cognitively stimulating experiences that might not be offered at home. These can help a child develop a strong foundation for thinking things through and foster an openness or motivation to learn. They can also involve teaching social and emotional skills to help manage one’s feelings, relate more effectively to others, see different perspectives and engage in effective problem-solving.

In addition, at-risk children who demonstrate impulsivity, attention deficits or difficult temperaments can be taught how to make healthy connections with others, including how to safely resolve conflicts. Chicago Child-Parent Centers are a good example of how to provide these interventions. They’ve been found to improve academic achievement among children as well as reduce the occurrence of crime in adulthood.

Interventions can also help parents. Teaching parents how to reduce harsh and ineffective parenting skills, utilize positive parenting practices — such as offering praise and encouragement — and engage in closer monitoring of their children are essential to helping children have a healthy view of themselves and the world.

Parents can also learn how to better handle their children’s tantrums, disobedience or defiance — such as rewarding children for appropriate or prosocial behaviors and administering negative consequences for inappropriate or other aggressive behaviors. Learning to set and consistently enforce limits helps children learn self-control and choose appropriate behavior. It also teaches children they are more likely to get what they want without violence and how to express difficult emotions without attacking others.

Meanwhile, school-based programs that help kids develop self-control and social competency skills have had positive effects on reducing the occurrence of aggression. After-school and community-based mentoring, such as providing recreation-based, drop-in clubs and tutoring services, may also assist in reducing youth engagement in delinquency and later offending. The rates of improvement vary and depend not only on the level of intervention but also the age of the child.

Kerig said there’s also some evidence for the effectiveness of these types of interventions for “callous-unemotional traits,” a subset of conduct disorder behaviors that are considered signs of serious psychopathy and a potential precursor to antisocial behavior. Furthermore, the research indicates that “positive and warm relationships,” rather than punishment in the form of reprimands and negative consequences, have the greatest impact. “As these children are primarily motivated by self-interest, the best way to influence them appears to be making sure that they like the people around them,” according to a paper from the University of Oslo, so they show “consideration for them as someone they like.”

To be sure, pointing a gun at an adult and shooting her at point-blank range may be violence of greater caliber than what the research to date confirms is treatable. And I certainly don’t want to draw sweeping and overly upbeat conclusions saying that every individual can be rehabilitated.

Let’s use the energy from all our intense emotions about this tragic incident to advocate for this child getting the help he needs.

But whatever intervention is used, said Duke psychiatry professor Robin Gurwitch, “the earlier children and families seek mental health services, the better.” The sooner children at risk are engaged in interventions, the more likely good skills are to take root and blossom rather than allowing poor, ineffective or dangerous ones to develop and solidify.

Recommended

OpinionHow this old-fashioned eating disorder stereotype hurts people like me

OpinionOne more thing for Democrats to fix: the Republican Party

Because we have no idea at this point what the circumstances of the child who shot his teacher are or what other problems he might have, it is premature to speculate on the exact type of treatment required. But make no doubt, mental health intervention is needed, and there are treatments that can be drawn on to help him.

The reportedly intentional shooting of a teacher by a 6-year-old is awful and heartbreaking. Let’s use the energy from all our intense emotions about this tragic incident to advocate for this child getting the help he needs, in addition to the teacher, classmates and all in the community who have been affected.