The 50 Best Serial Killer Movies of All Time

As recently as 2017, it was estimated by one nonprofit organization studying unsolved murders in the FBI database that there may be as many as 2,000 serial killers active in the United States at any given time.

Suffice it to say, they’re not all the stuff of classic horror movie plotting. Few are cannibals. Few live in rambling old mansions with secret passages and a private dungeon in the basement. Even fewer leave behind fiendishly complex cryptographs for a harried, chainsmoking detective and his partner to debate over plates of greasy diner eggs and black coffee. The more frightening reality is that many of them pass as the “average” people we interact with every day. That’s how these stories seem to go: A serial killer is not the sinister-looking stranger who just rolled into town; it’s that quiet next door neighbor who “kept to himself, mostly.” But that’s not what you see in serial killer movies.

Perhaps that’s why cinema has such a fascination with the more grandiose, manic version of the serial killer—these stories thrill us even as they’re distracting us from the more pressing danger and mundanity of everyday evil. Regardless, the concept of “a killer on the loose” has been rich cinematic soil for almost as long as film has existed. Go all the way back to 1920’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and what you basically have is a serial killer story—albeit, one in which the murders are being carried out by a hypnotized somnambulist. But the point stands.

Below, we’ve gathered the 50 greatest films about serial killers: a nightmare gallery of murderers both fantastical and disturbingly everyday. Granted, there are a lot of films about people getting killed serially—too many to take into consideration and compare without some basic parameters. So, here’s how we’re defining the idea of serial killer movies.

The killers in these films must be human. Vampires, werewolves and giant sharks all kill serially, but they’re not “serial killers” per se.

The killers can’t possess any overt supernatural powers or abilities. They can’t be ghosts, or undead revenants. This means, for example, that Michael Myers of Halloween is still able to qualify, as he is definitely a human being, whereas Jason Voorhees of Friday the 13th or Freddy Krueger of A Nightmare on Elm Street do not, given that one is (at least eventually) an undead golem and the other is a supernatural dream monster. Even Art the Clown of the Terrifier franchise has long been outed as more supernatural monster than human serial killer, so he’s not here either.

Ultimately, these are all stories about genuine human beings, killing other human beings. Got it? There’s some obvious crossover with our list of the best slasher movies of all time, so be sure to check that out as well.

50. PiecesYear: 1982

Director: Juan Piquer Simón

Pieces is the sort of silly, head-scratching early ’80s slasher wherein it’s difficult to decide if the director is trying to slyly parody the genre or actually believes in what he’s doing. Regardless, Pieces is a delightfully stupid movie, featuring a killer who murders his mother with an axe as a child after she scolds him for assembling a naughty adult jigsaw puzzle. All grown up, he stalks women on a college campus and saws off “pieces” in order to build a real-life jigsaw woman. The film’s individual murder sequences are completely and utterly bonkers, the best one being a sequence in which the female lead is walking down a dark alley and is suddenly attacked by a tracksuit-wearing “kung fu professor” played by “Brucesploitation” actor Bruce Le. After she incapacitates him, he apologizes, saying he must have had “some bad chop suey,” and waltzes out of the movie. The whole thing takes less than a minute. Pieces also boasts one of the best film taglines of all time: “Pieces: It’s exactly what you think it is!” As schlock goes, it’s an unheralded classic. —Jim Vorel

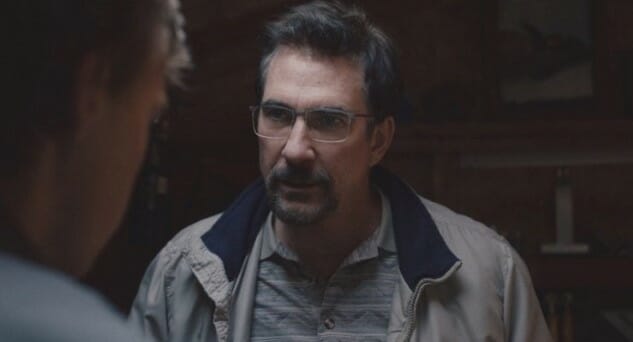

49. The Clovehitch KillerYear: 2018

Director: Duncan Skiles

Life in small-town Christian America can have a stultifying effect on a person, sucking out all personality and vitality, replacing all individual identity with better living through dogma. In The Clovehitch Killer, director Duncan Skiles replicates this bait-and-switch through cinematographer Luke McCoubrey’s camera. The film is shot stock-still, the camera more or less fixed from one scene to the next, as if affected by the vibe of routine humming throughout its setting of Somewhere, Kentucky. Almost none of the characters we meet in the movie have a spark; they’re drones tasked with maintaining the hive’s integrity against interlopers who, god forbid, actually bother to be somebody. Caught up in this dynamic is Tyler (Charlie Plummer), awkward, quiet and shy, the son of Don (Dylan McDermott), a handyman and Scout troop leader, which brings no end of unexpressed consternation to Tyler as a Scout himself. On the surface, Don looks and acts like an automaton, too, with occasional hints of humor and warmth in his capacity as father and Scoutmaster. Beneath, though, he’s something more, at least so Tyler suspects: The Clovehitch Killer, a serial killer who once tormented their area with a horrific murder spree long completed. Or maybe not. Maybe Don just has a real kink fetish and keeps rope around for fun in the bedroom. Either way, fathers aren’t always who or what they appear.

Horror movies are all about the squirm, the nerve-wracking build-up of tension over time that, done properly, leaves viewers crawling out of their skin with dread. In The Clovehitch Killer, this sensation is wrought entirely through craft instead of effects. That damn camera, motionless and unstirred, is always happy to film what’s in front of it, never one to pan about to catch new angles. What you see is what it shows you, but what it shows you might be more awful than you can stomach at a glance. This is a devilish movie that does beautifully what horror films are meant to—vex us with fear—through the most deceptively simple of means. —Andy Crump

48. The HitcherYear: 1986

Director: Robert Harmon

In horror films, there’s something alluring to a relentless and unstoppable killer whose motivation is only to destroy innocent life with nihilistic, almost supernatural fervor. Part of the reason the original Halloween is still so frightening lies in its chillingly effortless ability to present Michael Myers as a figure of death itself: no reason, no rhyme, he won’t stop until you stop breathing. The original The Hitcher operates on many of the same levels, as the simplicity of its premise about a couple (C. Thomas Howell and Jennifer Jason Leigh, who takes on a dual role, as the top and bottom halves of her body) hounded by a murderous maniac hitchhiker (Rutger Hauer) takes full advantage of the unresolved mystery surrounding the killer’s motivations. (Transform the truck from Duel into Rutger Hauer, and you get The Hitcher.) Director Robert Harmon’s film casts an appropriately icky, low-grade aura, perfectly fitting the killer’s philosophical point-of-view, an aesthetic approach that eludes the makers of the ill-fated 2007 remake, which looks too glossy to work on a visceral level. Also, with all due respect to Sean Bean, he’s no Rutger Hauer. —Oktay Ege Kozak

47. The Boy Behind the DoorYear: 2021

Director: David Charbonier, Justin Powell

The thing childhood abduction/serial killer story The Boy Behind the Door relies on the most is not nostalgia, though if you’re an adult, it may feel that way. The power of friendship is what keeps the heart of this film pumping fresh blood until the very end. There is something so sweet and unbreakable about a true childhood kinship, and that treasured bond is ripe between Bobby and Kevin. They are each other’s rock, and their dialogue and character impulses solidify this important piece of the puzzle that aids them throughout. Their mantra, “friends till the end,” sustains them through their trials and tribulations, and it is beyond clear that their symbiotic connection is their greatest asset. It’s easy, as a viewer, to feel deep catharsis with this element and your mind will wander back to those idyllic childhood moments with whomever was your best bud. But it seems the filmmakers also made it a point to take those feelings a step further: Their story makes you so thankful for those times, amid the uncertainty of life and the insidiousness of humanity, that the feeling will unsettle you. And, like The Boy Behind the Door, it should. —Lex Briscuso

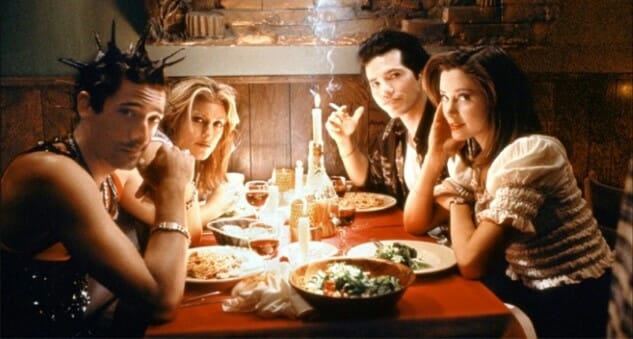

46. Summer of SamYear: 1999

Director: Spike Lee

Summer of Sam technically isn’t about the Son of Sam killer, who terrorized New York City during the summer of 1977 with his weapon of choice, a 44-caliber handgun— it’s a return for director Spike Lee to exploring how much irreversible damage unfounded paranoia and unchecked prejudice can inflict on neighborhoods, friendships and relationships. In a way, Summer of Sam operates as a mini-Do The Right Thing retread, focusing less overtly on race and more on how society marginalizes people who, for whatever reason, are different. When Richie (Adrian Brody) returns to his conservative Italian neighborhood dressing and acting like a proud member of a British punk band, the immediate reaction from his old friends is that he’s a freak, so he must be responsible for the murders that plague the city. Lee treating Son of Sam’s exploits as a sub-plot—Summer of Sam may feel a bit bloated and overlong, actually, with too many characters and sub-plots—actually works in heightening the visceral shock of the film’s killings: The death scenes lack the usual suspense of a standard serial killer flick, so that when the killer casually approaches his victims and empties his gun, the violence begins suddenly and ends suddenly, allowing us to contemplate the matter-of-factness of it, in direct contrast to more strangely macabre sequences, like when the killer has a conversation with a dog. —Oktay Ege Kozak

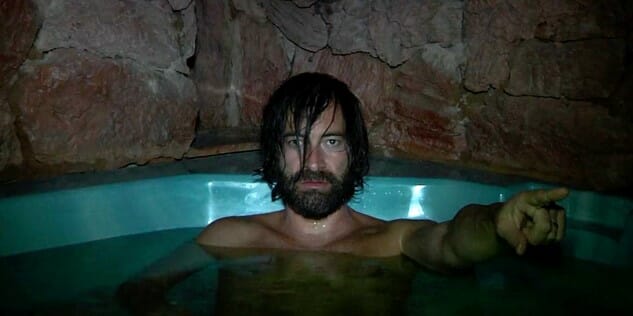

45. Creep 2Year: 2017

Director: Patrick Brice

Creep was not a movie begging for a sequel. About one of cinema’s more unique serial killers—a man who seemingly needs to form close personal bonds with his quarry before dispatching them as testaments to his “art”—the 2014 original was self-sufficient enough. But Creep 2 is that rare follow-up wherein the goal seems to be not “let’s do it again,” but “let’s go deeper”—and by deeper, we mean much deeper, as this film plumbs the psyche of the central psychopath (who now goes by) Aaron (Mark Duplass) in ways both wholly unexpected and shockingly sincere, as we witness (and somehow sympathize with) a killer who has lost his passion for murder, and thus his zest for life. In truth, the film almost forgoes the idea of being a “horror movie,” remaining one only because we know of the atrocities Aaron has committed in the past, meanwhile becoming much more of an interpersonal drama about two people exploring the boundaries of trust and vulnerability. Desiree Akhavan is stunning as Sara, the film’s only other principal lead, creating a character who is able to connect in a humanistic way with Aaron unlike anything a fan of the first film might think possible. Two performers bare it all, both literally and figuratively: Creep 2 is one of the most surprising, emotionally resonant horror films in recent memory. —Jim Vorel

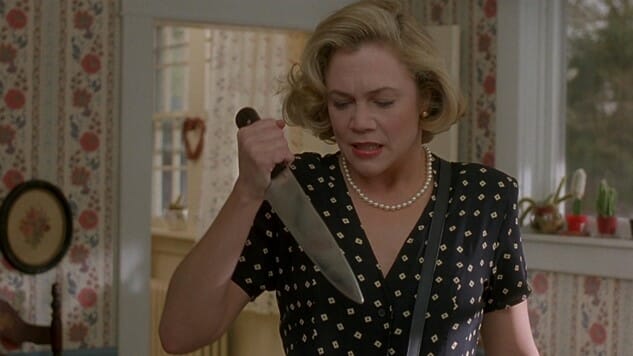

44. Serial MomYear: 1994

Director: John Waters

Ever the prescient scumbag sophisticate, John Waters presaged America’s true crime fixation—in the wake of the Menendez brothers and the Pamela Smart trials, before, even, Gus Van Sant’s groundbreaking To Die For, and in the glow of the OJ Simpson murders—with the tongue-through-cheek Serial Mom. Farce at the fore, Waters fully understands the power of having Kathleen Turner play the titular murderer, a woman whose attractiveness, domesticity and class status allow her the unearned sympathy and forgiveness her despicable crimes require in order to continue, but never shies away from juxtaposing the friendliness of Beverly Sutphin’s (Turner) demeanor with the putrid nature of her psyche, producing a film as upsetting as it is hilarious about the corrupt core of society’s cravings for such shitty stuff. Even as her family attempts to curb her homicidal ways, Beverly succeeds in ending the lives of those whose lives she wants to end, her husband (Sam Waterston) and daughter (Ricki Lake) and son (Matthew Lillard) helpless against the tide of ratings and Nielsen numbers working to thwart them. With little room for debate, Waters lays the blame for such blithe misery at our feet, insisting that with every bit of reality TV wretchedness we consume, we encourage another psychopath to take that extra step toward their own 15 minutes of sinister stardom. —Dom Sinacola