Angry Florida woman allegedly breaks into ex-boyfriend’s home, tosses pickled pork on couch, throws Sprite

A Florida woman was arrested after she broke into her ex-boyfriend’s home and spilled pickled pork on his couch before hitting him with a bottle of Sprite, according to the Lee County Sheriff’s Office.

Deputies released video of the ordeal involving Aukievah Reddick, 22.

On March 1, deputies with the Lee County Sheriff’s Office responded to an apartment complex for a reported break-in.

A doorbell camera caught Reddick taking the spare key from under the doormat and entering the home.

WASHINGTON DC THIEVES LEAVE VIDEO MESSAGE AMID CRIME SPREE: ‘I LOVE YOU DADDY’

Aukievah Reddick also threw a Sprite bottle at her ex during the altercation. (Lee County Sheriff’s Office)

Once deputies arrived, bodycam footage shows Reddick holding a bottle of Sprite outside the home, which she then allegedly threw at the victim, identified as her ex-boyfriend, and hit him. She also allegedly threw and broke items around the home.

Reddick began yelling at the victim and repeatedly said she wanted to fight him as the deputy tried to separate the pair.

COLORADO BURGLARY SUSPECT ARRESTED WHILE ON THE TOILET: ‘IN THE LINE OF DOODY’

Video shows an angry ex-girlfriend in Florida throwing a Sprite bottle at her ex-boyfriend after breaking into his home, throwing pickled pork onto a sofa and damaging the couch. (Lee County Sheriff’s Office)

The deputy is heard asking Reddick to go over by a tree away from the victim, so he could talk with the victim.

The suspect says she would listen to the deputy but points a finger at her ex-boyfriend, saying, “You, I’m not going to listen to.”

According to deputies, she even took a bottle of pickled pork and dumped it all over the victim’s couch.

A Florida woman was arrested for allegedly breaking into her ex’s home, throwing a Sprite bottle at the victim and pouring pickled pork on his sofa. (Lee County Sheriff’s Office)

Before authorities arrived, the man claimed Reddick texted him that she was coming over despite him not being home at the time, according to the affidavit obtained by WFLA.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Reddick was arrested and taken to the Lee County Jail for battery, burglary and criminal mischief, according to arrest records.

Stepheny Price is a Writer at Fox News with a focus on West Coast and Midwest news, missing persons, national and international crime stories, homicide cases, and border security.

A Timeline

By Denise Gee Peacock

On January 13, 1996, 9-year-old Amber Hagerman’s life was stolen by a stranger who dragged her kicking and screaming from her bicycle in broad daylight. Despite an unrelenting search and dedicated efforts by law enforcement, the media, and the public, Amber would never make it home. She was found brutally murdered. Her loss devastated her family and community, leaving a wound that has yet to heal.

In the months following the third-grader’s abduction and killing, Dallas-Fort Worth-area broadcasters worked with local police to establish what they hoped would be an antidote to future crimes: the America’s Missing: Broadcast Emergency Response (AMBER) Alert—named in Amber’s honor, both to remember her and to protect children in the future. It would harness the power of technology, the media, and community action to spread urgent news when a child’s life was in danger.

It took almost a decade to get every U.S. state to adopt the alert system, but as of Dec. 18, 2025, AMBER Alerts have helped recover more than 1,292 children nationwide—241 of them rescued because of wireless emergency alerts (WEAs).

Though Amber’s life was heartbreakingly short, her legacy has been to save countless lives. Each time an AMBER Alert flashes across a screen or sounds on a phone, her name is carried forward—not just as a reminder of tragedy, but as a symbol of hope, protection, and action.

Janell RasmussenAdministrator, AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program / Director, National Criminal Justice Training Center

Amber’s case also underscores fundamental lessons that child protection professionals should consider as they navigate missing child incidents.

Rapid public communication is vital.

Before Amber’s case, police lacked a formal framework for instantly broadcasting information about child abductions to the public.

The AMBER Alert system was created specifically to fill this gap, leveraging radio, TV, and eventually wireless technology to send out critical information like descriptions of the child, suspect, and vehicle.

“Amber’s case was a witnessed abduction—the rarest of all—and there was credible information available about the suspected abductor and his truck,” says Chuck Fleeger, Region 3 Liaison for the AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program (AATTAP). “There just wasn’t a mechanism then to get that information out quickly and to the widest possible audience.”

AATTAP’s Region 3 spans 10 states, from Louisiana to Nebraska to Arizona. It also encompasses Fleeger’s home state of Texas, where since 2003 he has served as executive director of the AMBER Alert Network Brazos Valley, a non-profit in central Texas that assists with regional AMBER Alert coordination, provides public education, and partners with local law enforcement and other responders in alerting, response, and investigative readiness.

In 2020 Fleeger retired as Assistant Chief of Police with the College Station Police Department, where he served for more than three decades. He now teaches AMBER Alert investigative best practices courses for the AATTAP.

Time is of the essence.

Experts recognized that the first few hours are the most critical in a child abduction case. The AMBER Alert protocol emphasizes speed, ensuring that law enforcement, broadcasters, and transportation agencies react swiftly to reports.

Long-term cases like Amber Hagerman’s are solvable. Technology continues to evolve and so do peoples’ lives. People will decide to talk for whatever reason when circumstances change.

Chuck FleegerRegion 3 Liaison, AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program

Balancing that need for speed with a desire for accuracy can be a struggle for AMBER Alert Coordinators. “Law enforcement wrestles with the desire to verify information is complete and accurate, but then it’s not timely; conversely, you can have timely information but some of it’s not completely accurate. That’s OK. It’s better to get the process going even if an activation package isn’t perfect,” Fleeger says. “We all know how crucial time is, so any moments that can be saved could potentially make the difference in a child’s recovery.”

Successfully navigating such a high-stakes process “takes a combination of continuing education, experience, and good communication with others,” says Fleeger’s colleague Joan Collins, Liaison for AATTAP’s Region 1 (encompassing 11 states in the Northeast, from Maine to West Virginia).

Collins’ career has involved 39 years of work for Rhode Island law enforcement. She spent 28 of those years with the Rhode Island State Police, where she helped audit and train users of the Rhode Island Law Enforcement Telecommunications System (RILETS); was central to increasing the state’s various emergency alerts; managed the state’s sex offender/“Most Wanted” databases; and worked with the state’s Internet Crimes Against Children task force.

The creation of the AMBER Alert system has become an important public global safety tool for child abductions, and there is ongoing hope for the resolution of Amber Hagerman’s case. The goal is to safely recover an abducted child. The decisions made by AMBER Alert Coordinators are often stressful, made quickly and under pressure, following established protocols and using their best judgment based on the information at hand.

Joan CollinsRegion 1 Liaison, AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program

“Doing this line of work involves being an active listener—of knowing what questions to ask,” she says. Collins now teaches such AATTAP courses as AMBER Alert: To Activate or Not Activate as well as 911 Telecommunicators and Missing & Abducted Children (aka “911 T-MAC”).

Coordination is key.

The AMBER Alert system functions through the seamless cooperation of multiple groups, including law enforcement, broadcasters, transportation agencies, and the media.

Reviews of every alert help to improve the process over time by getting input from these various partners.

Collins recommends that partners include not only those within one’s own law enforcement agency, but also those from surrounding states (“with whom you’re likely to work with more often than not”). “It’s important to connect with your counterparts elsewhere and build relationships with them early so you can act together quickly and successfully,” she says. “It’s always a relief to know others are ready and willing to help out during times of high stress, and they in turn will appreciate your advice and support.”

Protocols must be followed carefully.

For any case—which can potentially become a high-profile one—there is a need for law enforcement to meticulously follow established protocols. This includes the difficult decisions an AMBER Alert Coordinator must make with the limited information available at the time, which may be criticized by the public later.

“With any missing child case, law enforcement should first assume the child is at risk until evidence presents otherwise,” Fleeger says.

He also recommends patrol first responders consider the long-term implications of their efforts, avoiding any pass-the-buck mentality of case stewardship. “Think about the officers dispatched to Amber’s case. They certainly didn’t know when they started their shift that three decades later the case would be unsolved—and how dramatically changed available resources and response models would become.” It’s essential to remember that “the right documentation of information really matters. And if we’re doing good, solid police work from the earliest moments, that work should stand the test of time and hold up well.”

Use targeted, advanced technology.

Modern AMBER Alerts benefit from geotargeting, which focuses alerts on the people most likely to have seen the child. This prevents citizens in a wider area from being desensitized and ignoring alerts.

The public can help.

AMBER Alert’s success is a testament to the power of community vigilance. It allows millions of people to serve as the “eyes and ears” for law enforcement by reporting tips to the authorities. To keep the public from “information burnout” on a case, Fleeger recommends using multiple photos of a missing child at different times. “If someone is scrolling through their feed on social media and see the same photo time and again, they’ll assume they’ve already read that information,” he says. “A new or different photo will make somebody pause and think, ‘I didn’t realize he is still missing.’ The goal is to keep the case a priority in the public’s mind until we can get that person found.”

Don’t assume benign circumstances.

Before the AMBER Alert system, bystanders witnessing a child struggling with an adult may have assumed it was a family dispute or the child misbehaving. Amber’s case highlights the danger of assuming an abduction is a benign event and reinforces the importance of reporting suspicious activity immediately—even if it seems inconsequential.

Collins refers to the barking dog analogy in her teaching. She encourages dispatchers in training to ask questions and gather more information. “For example, is the dog that someone is calling about normally outside barking, or does it rarely bark? This could indicate whether something unusual is occurring. It’s important not to make assumptions, as callers may have relevant information that can be discovered by asking further questions

Stranger abductions are real.

While statistically rare—the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children reports that stranger abductions account for 1% of reported abductions—they are a real danger. Amber’s case serves as a reminder of the vulnerability of children, especially when a predator targets them. According to NCMEC, victims are most often girls, and the average age for attempted abductions is 11 and completed abductions is 14.

Justice is a long process.

Despite the creation of a system that has saved countless lives, Amber’s murder remains unsolved decades later. The lesson is that the fight for justice continues, and the public can still assist by reporting any strange observations. “Long-term cases like Amber Hagerman’s are solvable,” Fleeger says. “Technology continues to evolve and so do peoples’ lives. People will decide to talk for whatever reason when circumstances change. Consider the Austin [Texas] yogurt shop murder case that was recently solved. You just never know.”

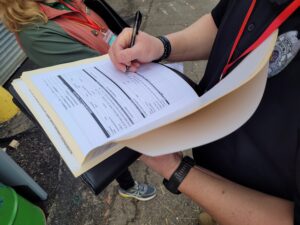

A year and a half ago, nationally recognized CART expert Stacie Lick became AATTAP’s CART Liaison.

James Holmes joins Stacie Lick in providing guidance from the perspectives of former CART Commanders who know the ins and outs of a rapid response team’s creation and sustainability.

Organizational charts help first responders see the big picture of how a CART will be structured during a missing child incident.

By Denise Gee Peacock

“Sometimes the solution to a problem is right in front of you, which may be a good sign you’re on the right track,” says Derek VanLuchene, AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program (AATTAP) Program Manager for child abduction response team (CART) training and certification.

VanLuchene’s task was to help others overcome a significant hurdle: “Certain CARTs were struggling with getting up and running, despite days of training and support. And our goal is, and always has been, to create more active teams across the country.”

With all that law enforcement agencies juggle and with seemingly fewer resources to tap, “maybe the agencies were just feeling overwhelmed,” VanLuchene says. Knowing that the burgeoning CARTs needed more follow-up and mentoring, one way to help struggling teams was to connect them with “the best of the best.” A year and a half ago, nationally recognized CART experts James Holmes and Stacie Lick became AATTAP’s CART Liaisons. Lick and Holmes now offer guidance to CARTs from the perspectives of former CART Commanders who know the ins and outs of a rapid response team’s creation and sustainability. So, problem solved, right?

Not quite. In some cases, fledgling CARTs also needed reminders of the core essentials needed to build a strong team. To resolve that, “maybe we needed to look again at how we were teaching the implementation course,” VanLuchene recalls.

For two decades, the AATTAP—part of the National Criminal Justice Training Center (NCJTC) of Fox Valley Technical College—has been providing CART training and certification support funded by the U.S. Department of Justice. The process for managing and updating its training curriculum involves continually reviewing participant evaluation feedback, current research and case law, updated investigative resources, case studies, current trends, relevant adult learning strategies, input from subject matter experts, and more.

As a result, scores of CARTs have received assistance to create (and ultimately, federally certify) an effective, efficient, organized response team prepared for a missing child incident.

A eureka moment hit VanLuchene last fall, when he found himself updating the CART program’s two essential instructional manuals (see related sidebar, page 9) streamlining their content for ease of understanding.

Essential to any CART’s implementation are “12 Core Components” (see related sidebar)—which include agreed-upon deployment criteria, experienced and committed team members, well- crafted callout methods, and the like. But as important as those core concepts are, it dawned on VanLuchene that the instructional module centered on them received only two hours of focus time during three days of CART training. Perhaps that’s why the essential information wasn’t sticking, he wondered. They needed to spend more time on the components. “And frankly, while the old curriculum was good stuff, those components were worthy of their own course—or at least an updated course,” VanLuchene says.

After discussing it with AATTAP Curriculum Manager Cathy Delapaz and Deputy Administrator Byron Fassett, the group agreed. “Derek’s observation was brilliant,” Fassett recalls. As a team they set out to restructure the CART implementation course. The 12 Core Components would be front and center throughout a new two-day intensive course. What’s more, the class wouldn’t just address CART theory and best practices, “it would become a hands-on workshop, one in which the 12 Core Components are used to actually create a working CART in real-time,” VanLuchene says.

A Three-Pronged Approach

The reformatted curriculum—the CART- smart restart, if you will—is achieved via a three-pronged approach to building a CART in real-time as opposed to discussing its eventual creation.

The first prong involves a pre-meeting with agency stakeholders who will review the types of CART members that are needed and resources available. “That’s when we confirm that they’re ready to make the CART happen via the second prong of planning”—the new two-day class, or workshop, on the 12 Core Components—a deep dive into a successful CART’s key ingredients, which can be applied to the agency’s matrix of strategic personnel through a sample organizational flow chart that’s proven its value in CARTs across the country. “This way they can better visualize and understand the CART’s standard operating procedure (SOP),” VanLuchene says.

The third prong is a post-workshop meeting to confirm the CART team members and resources; it also includes mentoring from VanLuchene and one of the AATTAP Liaisons to help tie up any loose ends in CART configuration. “After all the prep work we’ve provided, when they come out the other side, they’ll be ready,” he says.

Louisiana as Pilot Project

Nine months ago, Louisiana State Police (LSP) Captain Jay Donaldson, who oversees Region 3 Criminal Investigations, was tasked by his superiors to form a statewide CART team that could work independently in each of the state’s three regions while also working as a cohesive whole in case of a major disaster involving missing people (one on the scale of Hurricane Katrina, he notes).

To create the regional/state CART, Donaldson knew right where to turn: to Derek VanLuchene, whom he had gotten to know over the years during various AATTAP-NCJTC trainings. Progress was swift, VanLuchene says. “No grass was growing under their feet; they wanted to get right on it.” The meetings took place over a four-month period, “which was fantastic considering some CARTs can take a year or more to form.”

After hearing about the updated CART curriculum, Donaldson was eager to get started. The first meeting was on February 19, with the more intensive hands-on sessions occurring on May 28 and 29. “I’m more of a workshop person myself,” Donaldson recalls of the two-day workshops. “I was just hoping everyone else on our teams would be too. Thankfully they were.”

With Louisiana serving as the new pilot project for the CART course that would soon play out around the country, Donaldson watched closely.

“What Derek did for us was exceptional,” Donaldson says. “Whenever we were doing tabletops, he broke us up by region. He said, ‘let’s put people together who are going to actually work together. That way we’ll see what happens, what ideas form.’ And then, once he did that, everything just started working, everything just started clicking.”

Finding the right people to be involved in planning and execution of the CART details is crucial. In any agency, people will do things because they’re told to. Then they’ll want to do so because their heart is in the mission. The commitment Donaldson witnessed in the room during the two-day planning session “had me realizing we had all the people whose hearts would be in the right place,” he says.

Donaldson had faith that the new way of learning-by-doing was working not only for his team, but also for others.

VanLuchene was equally pleased: “If they get a call tomorrow about a missing child, they could activate their CART team in whatever region it was needed. Their organizational chart is in place, their SOP is in place. They’re ready for deployment.”

Smart Solutions Ahead

A key obstacle to creating a CART is falling prey to misconceptions surrounding them. Some administrators may look at a CART as another task force that needs to be managed—without the budget or staffing to do so. They need as many resources as possible for their regular caseload of crimes.

“But in helping teams formulate a CART, we’re not asking people to suddenly put aside their normal duties. We’re asking people to think differently about how they work together on a missing child case,” VanLuchene says.

“Why not take the 12 Core Components of a CART and apply them to your response so you get the most effective, organized, efficient outcome?” he asks. “It’s just that simple.”

In other cases, where there are preexisting major incident response teams to tackle emergencies, those groups of responders can learn the 12 components of a successful CART and walk away with an SOP. “You become an active CART team based on your ability to respond to cases involving missing kids,” VanLuchene says.

Finding the resources can also seem overwhelming until stakeholders are invited to become a part of the process, says LSP Captain Donaldson. He cites one partnership in particular. “We invited the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries to be involved in the training for the first time,” he says. “They were keen to observe and see if being in a CART was a space they wanted to share with us.”

That decision would be a natural. “Louisiana has so many bodies of water, and these guys know the camps or lakes or rivers or streams—which is where a child with autism, for instance, may be drawn to after a wandering incident,” Donaldson says. “And thankfully, they’re all in. They have the tools and resources, and these guys love what they do. Now they’re waiting for a mission. They’re all about saving children, if they can.”

The methodology for the new CART implementation course will also be used for AMBER Alert in Indian Country (AIIC) trainings. AIIC Program Manager Tyesha Wood and her team are currently observing the new curriculum in action and will be applying it to a forthcoming Tribal Response to Abducted Children (TRAC) initiative, which will help Tribal law enforcement bridge any gaps in child recovery knowledge and planning.

Meanwhile, CART Liaisons Lick and Holmes are working daily to ensure all current CARTs and ones in the making are taken care of. Both have managed CART teams so they relate to others’ challenges. “They say, ‘Here’s what we recommend based on our experience,’ ” VanLuchene says. “The Liaisons are helping bring the total CART training package together.”

Derek VanLuchene understands the audience; he relates well to police officers. I like the way he delivers training. It’s more conversational, more engaging.

Captain Jay DonaldsonLouisiana State Police

12 Core Components of a CART

- Response Criteria: This is a memorandum of understanding about the CART’s criteria and area of service and should have complete buy-in by all of the stakeholders involved

- Team Composition: The predetermined callout team should include an experienced and committed group of subject matter experts in areas including search and rescue, interview and interrogation, expert witness testimony, command post operations, major case investigations (including cold cases), and more.

- Notification and Deployment Protocols: For the CART to respond in a quick, preestablished timeframe, it must have a well-constructed and agreed-upon method to activate the callout and an updated list of contacts.

- Communications: Each team should have a plan for how it will communicate with the CART commander, command post, and others during an activation. This includes having a well-staffed call center for public tips and dedicated personnel monitoring social media accounts. A leads tracking and management system is crucial for disseminating leads for follow-up.

- Command and Control: This involves the structuring and outfitting of a command center, incident command system (command structure), and operational team leaders (search leads, volunteer management, and others).

- Search, Canvass and Rescue Operations: Establish a plan for searching, canvassing, and rescuing that includes response time and deployment logistics, as well as tactics for the successful use of volunteers with predetermined tasks.

- Training: Individual and CART agency training provides an opportunity for the team to test activation and callout procedures, revise rosters and contact information, update team members’ training and specialized skill records, inspect equipment inventory, adjust assignments, and review protocols.

- Legal Support: The goal in an endangered missing or abducted child case is to rescue the child, develop a solid prosecutorial case against the offender, and do both without violating the constitutional rights of members of the community. Issues such as search and seizure and the role of the prosecutor in the CART command post should be incorporated into the CART protocols. Every CART should include a prosecutor and/or legal adviser who should be involved in all trainings.

- Equipment/Resources Inventory. The inventory list goes well beyond tangible deployment needs, but includes detailed instructions on how every possible resource (including experts not part of the CART core team) can be accessed regardless of time or day. Every resource should have backup contact information (telephone and email), as well as procedures for making an after-hours callout.

- CART Protocols: Established protocols, along with operating procedures and manuals, will help ensure consistency in a CART’s functionality. These documents must be shared among and accepted by all participating agencies, and any changes to policies and procedures must be documented in a consistent, singular location.

- Victim Assistance and Reunification: When a child is recovered, it is critical for a variety of services to be made available as soon as possible—not only to address and physical/medical needs, but also the psychological distress resulting from the incident.

- Community: Utilizing members of the team to provide training and awareness to the public may generate volunteering when an incident occurs.

— From A Guide to CART Program Components and Implementation.

>> Find AATTAP’s two recently updated implementation- and certification- focused guides at AMBERAdvocate.org/CART/resources.

>> Find all the information you need to stay up to date on CART training objectives at AMBERAdvocate.org/CART/training

The simple path forward was not to reinvent the wheel. You just learn the CART process and 12 components—and apply them.

Derek VanLucheneAATTAP CART Program Manager

By Jody Garlock

Engaging the public has always been at the heart of AMBER Alerts. The program, after all, was built on the premise of instantly galvanizing citizens and motorists to serve as an extra set of eyes to help law enforcement safely locate an endangered missing or abducted child. The power of that concept played out literally and figuratively in a case that gripped the quiet county-seat town of Fallon, Nevada.

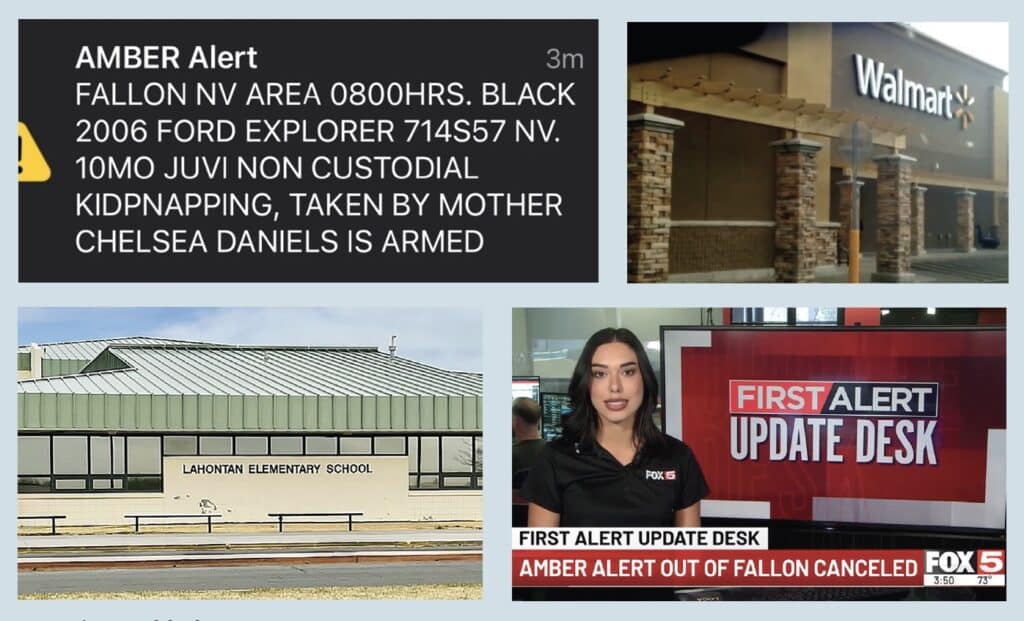

On March 31, 2025, the Nevada Department of Public Safety issued an AMBER Alert that was disseminated to broadcast media and cellular devices around Washoe County. Ten-month-old Lyric Smitten had been taken by his noncustodial mother, Chelsea Daniels, earlier that day. According to information released by the Churchill County Sheriff’s Office, authorities were advised that Daniels had been distraught after a court removed the boy from her care and custody. She was reported to have a handgun and had threatened to harm herself and her son.

The case solidly met the criteria for activating an AMBER Alert. These criteria included the belief that the child was in imminent danger and there was enough descriptive information for the public to aid in the recovery.

Unlike most AMBER Alerts, this case had an additional layer of urgency: The child was scheduled to undergo heart surgery the following day.

As news of the missing boy quickly spread around Fallon and the other high desert communities of western Nevada, tips to 911 came in. Because the vehicle Daniels was driving was relatively common—a black SUV (specifically a Ford Explorer) with a Nevada license plate— several tips matched a general description.

Although the AMBER Alert provided the license plate number, motorists aren’t always able to capture the exacting details. Officers knew the dire situation required taking all tips seriously, even those where the information matched just a general description of the SUV. One such tip led to a Fallon elementary school being placed on lockdown until authorities confirmed that the vehicle reported on the grounds wasn’t Daniels’.

One particular tip, however, stood out. A caller reported seeing a vehicle matching the description and that was being driven by a woman in an area that aligned with earlier cell phone pings from the mother’s phone. Patrol and investigative units were already in the area and took swift action. They spotted the SUV traveling on a mountain road.

After initially failing to stop, Daniels pulled over the vehicle, heeding the emergency lights and sirens from a sheriff’s deputy’s patrol vehicle. The infant was found safe; emergency medical responders also assessed the child’s health.

Authorities did not release information on the boy’s heart condition or surgery.

The Fallon Police Department took Daniels into custody on various charges, including kidnapping. Fallon authorities noted after the incident that concern about the child’s medical condition played a factor in the case rising to the level of an AMBER Alert.

Similar to how the public responded with tips, local authorities were quick to praise the public for its vigilance that contributed to the safe resolution. Churchill County Sheriff Richard Hickox also credited the multiple agencies and emergency medical responders who were involved. “We are grateful for the citizens who called in with sightings and information,” Hickox posted on Facebook. “The successful resolution of this situation is a prime example of a collaborative effort by many agencies striving toward one goal—and that is the safety of the public.”

Residents greeted news of the child’s safe recovery with similar gratitude. “Thank you to the people who spoke up and reported!” one person wrote on the Churchill County Sheriff’s social media page.

Carri Gordon, AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program (AATTAP) Liaison for Region 5 (which includes Nevada), considers the case an example of the AMBER Alert system working as it was intended: by engaging the public to prompt a swift recovery. “I’ve activated alerts in the past where the tip came in within six minutes of the Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) hitting cell phones, and it was from someone directly behind the suspect’s vehicle,” she recalls. “Law enforcement contacted and safely recovered that child in less than 15 minutes of the AMBER Alert going out. It’s literally lifesaving.”

During her 13 years as the state of Washington’s AMBER Alert Coordinator (AAC), Gordon handled more than 100 AMBER Alerts. Although alert activations for noncustodial parent abductions, such as in this case, have always been higher than stranger abductions, she reminds AACs that this doesn’t mean the child is free of danger. “Parents will—and do— harm their own children,” she says, dispelling a common misconception.

Gordon also knows from experience the pressure AACs feel every time an AMBER Alert is issued, even though they aren’t directly investigating the case. “As AACs we monitor our alerts as they go out and monitor the involvement on social media, such as the shares and likes,” she says. “When you see a case with a lot of public involvement—and tips that eventually lead to the location of the child—it makes you aware of how critical and valuable a tool like the AMBER Alert system is.”

Law enforcement relies on the public to be on the lookout for critically endangered missing and abducted children. This case illustrates how critical it is to follow those leads.

Carri GordonAATTAP Region 5 Liaison and former AMBER Alert Coordinator

In 2023, 59% of AMBER Alerts were for family abduction cases, according to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. The abductions tend to occur at transition points, such as when court-ordered exchanges of the child are scheduled to take place.

Tim Williams, center, manager of the New York State Missing Persons Clearinghouse (NYSMP) checks progress with David Fallon, retired FBI investigator and NCJTC-AATTAP Associate.

: Intelligence Analyst Joy Johnston of the New York State Police answers questions during a rescue operation to locate children reported missing as runaways.

Samuel Lizzio and Mark Baney, New York State Police senior investigators, work a case. In 2024, New York closed 12,310 cases involving children reported missing as runaways, according to the Division of Criminal Justice Services.

Alan Lapage, NYSMPC investigative supervisor, rings a bell to signal a missing child was safely located.

By Jody Garlock

It’s an early morning in March, and about 100 law enforcement officials, social services professionals, legal experts, and others are gathered in a hotel ballroom in Latham, New York. Wearing lanyards with name tags and sitting at tables with laptops and papers in front of them, they seem poised for a routine conference. But there’s a seriousness in the air and laser focus as they work on their computers or huddle into small groups.

Eventually, the ringing of a bell sounds across the room. Heads turn toward a man holding a brass school bellas the realization sets in: A missing child has been located.

By the end of the three-day Capital Region Missing Child Rescue Operation, that bell will have been rung an impressive 63 times. Simultaneously, a computer screen projected onto a wall showed the number in big, bold lettering. Both served as uplifting motivators for the agencies and experts who united for a goal of finding missing children at risk of endangerment, exploitation, or harm. “After the first or second bell ring, everyone gets it—it’s powerful,” says Tim Williams, manager of the New York State Missing Persons Clearinghouse (NYSMPC), one of organizers. “You could feel the energy in the room continue to increase.”

More than 60 local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies, nonprofit organizations, and private partners came together to explore new leads, review case notes, and leverage technology to find at-risk youth reported missing as runaways.

The 63 children and teens located during the first-ever rescue operation for the Albany, Schenectady, and Troy areas ranged in age from 2 to 17 years old when they were reported

missing, and from 6 to 22 when found, according to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS). And the overall number of those safely located continued to climb, as work that was started wrapped up after the event. Williams says 71 missing children have now been located as a direct result of the rescue operation.

“These are emotional events,” says Kevin Branzetti (shown below right under quote), CEO of the National Child Protection Task Force (NCPTF), which partnered with NYSMPC on the operation and has similar recovery missions scheduled in other states.

“We know these cases can be emotional roller coasters. You see a lot of tears.”

To drive home the importance of such ventures, Branzetti and Williams point to statistics. At the end of 2024, New York had slightly more than 1,000 active missing children cases. The majority of the 12,000-plus cases annually—95 percent— are reported as runaways.

“Every missing child is an endangered missing child,” Williams says. “Our focus was the runaway population because it’s often overlooked.”

Strategic Teamwork

The Capital Region event grew out of training sessions between NYSMPC and the Arkansas-based NCPTF. “We started to think ‘Could we put all these people in the same room with the sole mission of finding kids and closing cases?’ “ Williams says.

In October 2024, NYSMPC and NCPTF spearheaded their first joint rescue operation. That venture in the Buffalo area safely located 47 children reported missing as runways. Branzetti and Clearinghouse staffers, including Williams and Cindy Neff, who recently retired as NYSMPC manager, applied lessons they learned from the Buffalo operation. Comparatively, the Capital Region operation was more complex, involving coordination among three police departments, three district attorney’s offices, and three county social services agencies, along with many other entities.

“One of the most critical components is securing full buy-in from local partners, law enforcement, social services, district attorneys, and child advocacy centers,” Neff says. “Their collaboration is essential because these operations go beyond just locating missing youth. It’s also about understanding the underlying reasons they went missing and identifying the support needed to help prevent it from happening again.” (For more on Neff see the sidebar that follows this feature.)

The Capital Region operation required months of planning and meetings to review cases with agencies and coordinate logistics. Participants were ultimately organized into four teams— two for Albany and one each for Schenectady and Troy. A pre-operation meeting was held for all the teams prior to the operation.

Each team had a similar composition: a Clearinghouse representative who acted as the organizer, a crime analyst who had access to local police records, at least one detective from the agency working the case, representatives from NCTPF and the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), a probation official, someone from social services, and various other law enforcement officials. The goal was to ensure that each team had a variety of resources and skill sets, be it public records searching, tracking a cell phone, understanding social media work, or open-source intelligence. “No two police departments have the same sets of tools,” Branzetti says. “Everyone brings their tools to the game, and we get to share them.”

Adding a social services component—and having those professionals in the room prepared to go out when a child was recovered—was one of the lessons learned from the prior operation. Branzetti, Williams, and Neff note that the goal wasn’t just to find the child, but also to try to ensure the child doesn’t go missing again. “What we promote deeply is ‘Find. Listen. Help,’ “ Branzetti says. “It takes more than police to do that. It’s a society problem.”

The state’s Office of Children and Family Services coordinated with nonprofit organizations and victim assistance programs to assist the investigations and provide services and support for recovered children. “There was a whole support-service side of this ready to go and available—and put into action many times,” Williams says. If a child already had an assigned case worker, that person was notified.

A unique component was providing gift cards to ensure a child or teen had essentials, such as food, clothing, or haircare services. In some cases, the gift cards became an outreach opportunity for the social services worker to schedule a follow-up to take a teen shopping. “We wanted her to see that something is different today,” says Branzetti, whose organization secured donations to provide the gift cards. “We wanted her to understand that this isn’t the same old story. It’s about changing the trajectory.”

Additionally, the rescue operation also helps destigmatize the word “runaway.” “It’s a matter of changing the mindset of what that means,” Williams says.

“Everyone in the room is getting a better sense of the word as they work on the cases and realize that we can’t treat a runaway as ‘I’ll get to it when I get to it’ and instead say ‘Let’s make sure we’re doing something.’ “

‘Remarkable’ Collaboration

Heading into the rescue operation, the organizers didn’t have a set goal for the number of children they wanted to find. “If we can find even one missing child, that’s a positive,” Williams says. Because team members had started pre-work, some of the cases were able to be swiftly closed. A side benefit, Branzetti says, is that the rescue operation helps broaden or hone skills, and participants leave with added knowledge they can apply to their own cases. “These rescue operations turn into partial training events,” he says. “You actually may be writing a first search warrant or doing a first cell tower dump, or someone is walking you through how to track an IP address. You can’t beat that.”

The organizers also note that it’s heartening to see the camaraderie develop on the mixed teams, where members typically start out the rescue operation as strangers.

Williams says the operation proved to him how beneficial it is to bring together diverse groups. “We all tend to fall into the silo that we’re comfortable in, but we hear so many times, ‘Oh I wish I had reached out to you sooner,’ ” he says. “Sitting down at the same table, talking through cases, and sharing resources that are available is so important. Don’t be afraid to have those difficult conversations or continue to talk weekly or monthly to stay on top of things.”

For Neff, the rescue operation was a gratifying culmination to her long career. “When professionals from different agencies are brought together in the same room with a shared mission,” she says, “remarkable things can happen.”

Every time a child runs away, it’s a cry for help. That child is screaming out for our help, and it’s our job to do something.

Kevin BranzettiCEO, National Child Protection Task Force

Empathy & Respect: Hallmarks of Cindy Neff’s Child Protection Career

For Cindy Neff, the Capital Region Missing Child Rescue Operation was a fitting end to a long career of helping children. In April, Neff retired from the New York State Missing Persons Clearinghouse, where she worked for 20 years—the past 11 years as manager. “She’s a force of nature,” says Kevin Branzetti, CEO of the National Child Protection Task Force who worked with Neff on the New York rescue operations and various other initiatives.

Over the years, Neff has been a familiar face at national AMBER Alert symposiums, serving as an Associate for NCJTC-AATTAP. She also led the charge for establishing the New York State Cold Case Review Panel and developing the Find Them web application to support law enforcement working missing persons cases.

The issue of children with multiple missing episodes has always been close to her heart. In New York, about half of the missing children classified as runaways involve repeat episodes. Neff likens it to her personal experience of her mother being shuffled from one nursing home to another until she landed in a place where she was treated with compassion and dignity. Like with her mother, she feels runaway children are placed wherever there is an open bed, not necessarily where they will receive the care and services they need.

To address the issue, she helped form a statewide partnership that promotes a systems-based approach to supporting vulnerable children. This led to launching RIPSTOP (Runaway Intervention Program: Services, Training, Opportunity, Prevention), which identifies root causes and connects youth to targeted services. The hope is that RIPSTOP becomes a model for the state.

“I believe it represents the future of how we must address missing child cases: with empathy, data-driven solutions, and collaboration across systems,” Neff says. “We must reject the mindset of ‘They’re just a runaway—they’ll come back.’ Every missing child is at risk until proven otherwise, and every case deserves our full attention.”

In her immediate retirement, Neff is recharging and enjoying time with her grandchildren. She also plans to thoughtfully consider how she may stay involved in the field in the future. She encourages fellow Clearinghouse managers and AMBER Alert Coordinators to carry on the mission on behalf of missing children by setting clear goals, regularly assessing priorities, and building strong partnerships at every level. “This work cannot be done in isolation,” she says.