Procedural Due Process Civil

SECTION 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

AnnotationsGenerally

Due process requires that the procedures by which laws are applied must be evenhanded, so that individuals are not subjected to the arbitrary exercise of government power.737 Exactly what procedures are needed to satisfy due process, however, will vary depending on the circumstances and subject matter involved.738 A basic threshold issue respecting whether due process is satisfied is whether the government conduct being examined is a part of a criminal or civil proceeding.739 The appropriate framework for assessing procedural rules in the field of criminal law is determining whether the procedure is offensive to the concept of fundamental fairness.740 In civil contexts, however, a balancing test is used that evaluates the government’s chosen procedure with respect to the private interest affected, the risk of erroneous deprivation of that interest under the chosen procedure, and the government interest at stake.741

Relevance of Historical Use.—The requirements of due process are determined in part by an examination of the settled usages and modes of proceedings of the common and statutory law of England during pre-colonial times and in the early years of this country.742 In other words, the antiquity of a legal procedure is a factor weighing in its favor. However, it does not follow that a procedure settled in English law and adopted in this country is, or remains, an essential element of due process of law. If that were so, the procedure of the first half of the seventeenth century would be “fastened upon American jurisprudence like a strait jacket, only to be unloosed by constitutional amendment.”743 Fortunately, the states are not tied down by any provision of the Constitution to the practice and procedure that existed at the common law, but may avail themselves of the wisdom gathered by the experience of the country to make changes deemed to be necessary.744

Non-Judicial Proceedings.—A court proceeding is not a requisite of due process.745 Administrative and executive proceedings are not judicial, yet they may satisfy the Due Process Clause.746 Moreover, the Due Process Clause does not require de novo judicial review of the factual conclusions of state regulatory agencies,747 and may not require judicial review at all.748 Nor does the Fourteenth Amendment prohibit a state from conferring judicial functions upon non-judicial bodies, or from delegating powers to a court that are legislative in nature.749 Further, it is up to a state to determine to what extent its legislative, executive, and judicial powers should be kept distinct and separate.750

The Requirements of Due Process.—Although due process tolerates variances in procedure “appropriate to the nature of the case,”751 it is nonetheless possible to identify its core goals and requirements. First, “[p]rocedural due process rules are meant to protect persons not from the deprivation, but from the mistaken or unjustified deprivation of life, liberty, or property.”752 Thus, the required elements of due process are those that “minimize substantively unfair or mistaken deprivations” by enabling persons to contest the basis upon which a state proposes to deprive them of protected interests.753 The core of these requirements is notice and a hearing before an impartial tribunal. Due process may also require an opportunity for confrontation and cross-examination, and for discovery; that a decision be made based on the record, and that a party be allowed to be represented by counsel.

(1) Notice. “An elementary and fundamental requirement of due process in any proceeding which is to be accorded finality is notice reasonably calculated, under all the circumstances, to apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action and afford them an opportunity to present their objections.”754 This may include an obligation, upon learning that an attempt at notice has failed, to take “reasonable followup measures” that may be available.755 In addition, notice must be sufficient to enable the recipient to determine what is being proposed and what he must do to prevent the deprivation of his interest.756 Ordinarily, service of the notice must be reasonably structured to assure that the person to whom it is directed receives it.757 Such notice, however, need not describe the legal procedures necessary to protect one’s interest if such procedures are otherwise set out in published, generally available public sources.758

(2) Hearing. “[S]ome form of hearing is required before an individual is finally deprived of a property [or liberty] interest.”759 This right is a “basic aspect of the duty of government to follow a fair process of decision making when it acts to deprive a person of his possessions. The purpose of this requirement is not only to ensure abstract fair play to the individual. Its purpose, more particularly, is to protect his use and possession of property from arbitrary encroachment . . . .”760 Thus, the notice of hearing and the opportunity to be heard “must be granted at a meaningful time and in a meaningful manner.”761

(3) Impartial Tribunal. Just as in criminal and quasi-criminal cases,762 an impartial decisionmaker is an essential right in civil proceedings as well.763 “The neutrality requirement helps to guarantee that life, liberty, or property will not be taken on the basis of an erroneous or distorted conception of the facts or the law. . . . At the same time, it preserves both the appearance and reality of fairness . . . by ensuring that no person will be deprived of his interests in the absence of a proceeding in which he may present his case with assurance that the arbiter is not predisposed to find against him.”764 Thus, a showing of bias or of strong implications of bias was deemed made where a state optometry board, made up of only private practitioners, was proceeding against other licensed optometrists for unprofessional conduct because they were employed by corporations. Since success in the board’s effort would redound to the personal benefit of private practitioners, the Court thought the interest of the board members to be sufficient to disqualify them.765

There is, however, a “presumption of honesty and integrity in those serving as adjudicators,”766 so that the burden is on the objecting party to show a conflict of interest or some other specific reason for disqualification of a specific officer or for disapproval of the system. Thus, combining functions within an agency, such as by allowing members of a State Medical Examining Board to both investigate and adjudicate a physician’s suspension, may raise substantial concerns, but does not by itself establish a violation of due process.767 The Court has also held that the official or personal stake that school board members had in a decision to fire teachers who had engaged in a strike against the school system in violation of state law was not such so as to disqualify them.768 Sometimes, to ensure an impartial tribunal, the Due Process Clause requires a judge to recuse himself from a case. In Caperton v. A. T. Massey Coal Co. , Inc., the Court noted that “most matters relating to judicial disqualification [do] not rise to a constitutional level,” and that “matters of kinship, personal bias, state policy, [and] remoteness of interest, would seem generally to be matters merely of legislative discretion.”769 The Court added, however, that “[t]he early and leading case on the subject” had “concluded that the Due Process Clause incorporated the common-law rule that a judge must recuse himself when he has ‘a direct, personal, substantial, pecuniary interest’ in a case.”770 In addition, although “[p]ersonal bias or prejudice ‘alone would not be sufficient basis for imposing a constitutional requirement under the Due Process Clause,’” there “are circumstances ‘in which experience teaches that the probability of actual bias on the part of the judge or decisionmaker is too high to be constitutionally tolerable.’”771 These circumstances include “where a judge had a financial interest in the outcome of a case” or “a conflict arising from his participation in an earlier proceeding.”772 In such cases, “[t]he inquiry is an objective one. The Court asks not whether the judge is actually, subjectively biased, but whether the average judge in his position is ‘likely’ to be neutral, or whether there is an unconstitutional ‘potential for bias.’”773 In Caperton, a company appealed a jury verdict of $50 million, and its chairman spent $3 million to elect a justice to the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia at a time when “[i]t was reasonably foreseeable . . . that the pending case would be before the newly elected justice.”774 This $3 million was more than the total amount spent by all other supporters of the justice and three times the amount spent by the justice’s own committee. The justice was elected, declined to recuse himself, and joined a 3-to-2 decision overturning the jury verdict. The Supreme Court, in a 5-to-4 opinion written by Justice Kennedy, “conclude[d] that there is a serious risk of actual bias—based on objective and reasonable perceptions—when a person with a personal stake in a particular case had a significant and disproportionate influence in placing the judge on the case by raising funds or directing the judge’s election campaign when the case was pending or imminent.”775

Subsequently, in Williams v. Pennsylvania, the Court found that the right of due process was violated when a judge on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court—who participated in case denying post-conviction relief to a prisoner convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death—had, in his former role as a district attorney, given approval to seek the death penalty in the prisoner’s case.776 Relying on Caperton, which the Court viewed as having set forth an “objective standard” that requires recusal when the likelihood of bias on the part of the judge is “too high to be constitutionally tolerable,”777 the Williams Court specifically held that there is an impermissible risk of actual bias when a judge had previously had a “significant, personal involvement as a prosecutor in a critical decision regarding the defendant’s case.”778 The Court based its holding, in part, on earlier cases which had found impermissible bias occurs when the same person serves as both “accuser” and “adjudicator” in a case, which the Court viewed as having happened in Williams.779 It also reasoned that authorizing another person to seek the death penalty represents “significant personal involvement” in a case,780 and took the view that the involvement of multiple actors in a case over many years “only heightens”—rather than mitigates—the “need for objective rules preventing the operation of bias that otherwise might be obscured.”781 As a remedy, the case was remanded for reevaluation by the reconstituted Pennsylvania Supreme Court, notwithstanding the fact that the judge in question did not cast the deciding vote, as the Williams Court viewed the judge’s participation in the multi-member panel’s deliberations as sufficient to taint the public legitimacy of the underlying proceedings and constitute reversible error.782

(4) Confrontation and Cross-Examination. “In almost every setting where important decisions turn on questions of fact, due process requires an opportunity to confront and cross-examine adverse witnesses.”783 Where the “evidence consists of the testimony of individuals whose memory might be faulty or who, in fact, might be perjurers or persons motivated by malice, vindictiveness, intolerance, prejudice, or jealously,” the individual’s right to show that it is untrue depends on the rights of confrontation and cross-examination. “This Court has been zealous to protect these rights from erosion. It has spoken out not only in criminal cases, . . . but also in all types of cases where administrative . . . actions were under scrutiny.”784

(5) Discovery. The Court has never directly confronted this issue, but in one case it did observe in dictum that “where governmental action seriously injures an individual, and the reasonableness of the action depends on fact findings, the evidence used to prove the Government’s case must be disclosed to the individual so that he has an opportunity to show that it is untrue.”785 Some federal agencies have adopted discovery rules modeled on the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and the Administrative Conference has recommended that all do so.786 There appear to be no cases, however, holding they must, and there is some authority that they cannot absent congressional authorization.787

(6) Decision on the Record. Although this issue arises principally in the administrative law area,788 it applies generally. “[T]he decisionmaker’s conclusion . . . must rest solely on the legal rules and evidence adduced at the hearing. To demonstrate compliance with this elementary requirement, the decisionmaker should state the reasons for his determination and indicate the evidence he relied on, though his statement need not amount to a full opinion or even formal findings of fact and conclusions of law.”789

(7) Counsel. In Goldberg v. Kelly, the Court held that a government agency must permit a welfare recipient who has been denied benefits to be represented by and assisted by counsel.790 In the years since, the Court has struggled with whether civil litigants in court and persons before agencies who could not afford retained counsel should have counsel appointed and paid for, and the matter seems far from settled. The Court has established a presumption that an indigent does not have the right to appointed counsel unless his “physical liberty” is threatened.791 Moreover, that an indigent may have a right to appointed counsel in some civil proceedings where incarceration is threatened does not mean that counsel must be made available in all such cases. Rather, the Court focuses on the circumstances in individual cases, and may hold that provision of counsel is not required if the state provides appropriate alternative safeguards.792

Though the calculus may vary, cases not involving detention also are determined on a casebycase basis using a balancing standard.793

For instance, in a case involving a state proceeding to terminate the parental rights of an indigent without providing her counsel, the Court recognized the parent’s interest as “an extremely important one.” The Court, however, also noted the state’s strong interest in protecting the welfare of children. Thus, as the interest in correct fact-finding was strong on both sides, the proceeding was relatively simple, no features were present raising a risk of criminal liability, no expert witnesses were present, and no “specially troublesome” substantive or procedural issues had been raised, the litigant did not have a right to appointed counsel.794 In other due process cases involving parental rights, the Court has held that due process requires special state attention to parental rights.795 Thus, it would appear likely that in other parental right cases, a right to appointed counsel could be established.The Procedure That Is Due Process

The Interests Protected: “Life, Liberty and Property”.— The language of the Fourteenth Amendment requires the provision of due process when an interest in one’s “life, liberty or property” is threatened.796 Traditionally, the Court made this determination by reference to the common understanding of these terms, as embodied in the development of the common law.797 In the 1960s, however, the Court began a rapid expansion of the “liberty” and “property” aspects of the clause to include such non-traditional concepts as conditional property rights and statutory entitlements. Since then, the Court has followed an inconsistent path of expanding and contracting the breadth of these protected interests. The “life” interest, on the other hand, although often important in criminal cases, has found little application in the civil context.

The Property Interest.—The expansion of the concept of “property rights” beyond its common law roots reflected a recognition by the Court that certain interests that fall short of traditional property rights are nonetheless important parts of people’s economic well-being. For instance, where household goods were sold under an installment contract and title was retained by the seller, the possessory interest of the buyer was deemed sufficiently important to require procedural due process before repossession could occur.798 In addition, the loss of the use of garnished wages between the time of garnishment and final resolution of the underlying suit was deemed a sufficient property interest to require some form of determination that the garnisher was likely to prevail.799 Furthermore, the continued possession of a driver’s license, which may be essential to one’s livelihood, is protected; thus, a license should not be suspended after an accident for failure to post a security for the amount of damages claimed by an injured party without affording the driver an opportunity to raise the issue of liability.800

A more fundamental shift in the concept of property occurred with recognition of society’s growing economic reliance on government benefits, employment, and contracts,801 and with the decline of the “right-privilege” principle. This principle, discussed previously in the First Amendment context,802 was pithily summarized by Justice Holmes in dismissing a suit by a policeman protesting being fired from his job: “The petitioner may have a constitutional right to talk politics, but he has no constitutional right to be a policeman.”803 Under this theory, a finding that a litigant had no “vested property interest” in government employment,804 or that some form of public assistance was “only” a privilege,805 meant that no procedural due process was required before depriving a person of that interest.806 The reasoning was that, if a government was under no obligation to provide something, it could choose to provide it subject to whatever conditions or procedures it found appropriate.

The conceptual underpinnings of this position, however, were always in conflict with a line of cases holding that the government could not require the diminution of constitutional rights as a condition for receiving benefits. This line of thought, referred to as the “unconstitutional conditions” doctrine, held that, “even though a person has no ‘right’ to a valuable government benefit and even though the government may deny him the benefit for any number of reasons, it may not do so on a basis that infringes his constitutionally protected interests—especially, his interest in freedom of speech.”807 Nonetheless, the two doctrines coexisted in an unstable relationship until the 1960s, when the right-privilege distinction started to be largely disregarded.808

Concurrently with the virtual demise of the “right-privilege” distinction, there arose the “entitlement” doctrine, under which the Court erected a barrier of procedural—but not substantive—protections809 against erroneous governmental deprivation of something it had within its discretion bestowed. Previously, the Court had limited due process protections to constitutional rights, traditional rights, common law rights and “natural rights.” Now, under a new “positivist” approach, a protected property or liberty interest might be found based on any positive governmental statute or governmental practice that gave rise to a legitimate expectation. Indeed, for a time it appeared that this positivist conception of protected rights was going to displace the traditional sources.

As noted previously, the advent of this new doctrine can be seen in Goldberg v. Kelly,810 in which the Court held that, because termination of welfare assistance may deprive an eligible recipient of the means of livelihood, the government must provide a pretermination evidentiary hearing at which an initial determination of the validity of the dispensing agency’s grounds for termination may be made. In order to reach this conclusion, the Court found that such benefits “are a matter of statutory entitlement for persons qualified to receive them.”811 Thus, where the loss or reduction of a benefit or privilege was conditioned upon specified grounds, it was found that the recipient had a property interest entitling him to proper procedure before termination or revocation.

At first, the Court’s emphasis on the importance of the statutory rights to the claimant led some lower courts to apply the Due Process Clause by assessing the weights of the interests involved and the harm done to one who lost what he was claiming. This approach, the Court held, was inappropriate. “[W]e must look not to the ‘weight’ but to the nature of the interest at stake. . . . We must look to see if the interest is within the Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of liberty and property.”812 To have a property interest in the constitutional sense, the Court held, it was not enough that one has an abstract need or desire for a benefit or a unilateral expectation. He must rather “have a legitimate claim of entitlement” to the benefit. “Property interests, of course, are not created by the Constitution. Rather, they are created and their dimensions are defined by existing rules or understandings that stem from an independent source such as state law—rules or understandings that secure certain benefits and that support claims of entitlement to those benefits.”813

Consequently, in Board of Regents v. Roth, the Court held that the refusal to renew a teacher’s contract upon expiration of his one-year term implicated no due process values because there was nothing in the public university’s contract, regulations, or policies that “created any legitimate claim” to reemployment.814 By contrast, in Perry v. Sindermann,815 a professor employed for several years at a public college was found to have a protected interest, even though his employment contract had no tenure provision and there was no statutory assurance of it.816 The “existing rules or understandings” were deemed to have the characteristics of tenure, and thus provided a legitimate expectation independent of any contract provision.817

The Court has also found “legitimate entitlements” in a variety of other situations besides employment. In Goss v. Lopez,818 an Ohio statute provided for both free education to all residents between five and 21 years of age and compulsory school attendance; thus, the state was deemed to have obligated itself to accord students some due process hearing rights prior to suspending them, even for such a short period as ten days. “Having chosen to extend the right to an education to people of appellees’ class generally, Ohio may not withdraw that right on grounds of misconduct, absent fundamentally fair procedures to determine whether the misconduct has occurred.”819 The Court is highly deferential, however, to school dismissal decisions based on academic grounds.820

The further one gets from traditional precepts of property, the more difficult it is to establish a due process claim based on entitlements. In Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales,821 the Court considered whether police officers violated a constitutionally protected property interest by failing to enforce a restraining order obtained by an estranged wife against her husband, despite having probable cause to believe the order had been violated. While noting statutory language that required that officers either use “every reasonable means to enforce [the] restraining order” or “seek a warrant for the arrest of the restrained person,” the Court resisted equating this language with the creation of an enforceable right, noting a longstanding tradition of police discretion coexisting with apparently mandatory arrest statutes.822 Finally, the Court even questioned whether finding that the statute contained mandatory language would have created a property right, as the wife, with no criminal enforcement authority herself, was merely an indirect recipient of the benefits of the governmental enforcement scheme.823

In Arnett v. Kennedy,824 an incipient counter-revolution to the expansion of due process was rebuffed, at least with respect to entitlements. Three Justices sought to qualify the principle laid down in the entitlement cases and to restore in effect much of the right-privilege distinction, albeit in a new formulation. The case involved a federal law that provided that employees could not be discharged except for cause, and the Justices acknowledged that due process rights could be created through statutory grants of entitlements. The Justices, however, observed that the same law specifically withheld the procedural protections now being sought by the employees. Because “the property interest which appellee had in his employment was itself conditioned by the procedural limitations which had accompanied the grant of that interest,”825 the employee would have to “take the bitter with the sweet.”826 Thus, Congress (and by analogy state legislatures) could qualify the conferral of an interest by limiting the process that might otherwise be required.

But the other six Justices, although disagreeing among themselves in other respects, rejected this attempt to formulate the issue. “This view misconceives the origin of the right to procedural due process,” Justice Powell wrote. “That right is conferred not by legislative grace, but by constitutional guarantee. While the legislature may elect not to confer a property interest in federal employment, it may not constitutionally authorize the deprivation of such an interest, once conferred, without appropriate procedural safeguards.”827 Yet, in Bishop v. Wood,828 the Court accepted a district court’s finding that a policeman held his position “at will” despite language setting forth conditions for discharge. Although the majority opinion was couched in terms of statutory construction, the majority appeared to come close to adopting the three-Justice Arnett position, so much so that the dissenters accused the majority of having repudiated the majority position of the six Justices in Arnett. And, in Goss v. Lopez,829 Justice Powell, writing in dissent but using language quite similar to that of Justice Rehnquist in Arnett, seemed to indicate that the right to public education could be qualified by a statute authorizing a school principal to impose a ten-day suspension.830

Subsequently, however, the Court held squarely that, because “minimum [procedural] requirements [are] a matter of federal law, they are not diminished by the fact that the State may have specified its own procedures that it may deem adequate for determining the preconditions to adverse action.” Indeed, any other conclusion would allow the state to destroy virtually any state-created property interest at will.831 A striking application of this analysis is found in Logan v. Zimmerman Brush Co.,832 in which a state anti-discrimination law required the enforcing agency to convene a fact-finding conference within 120 days of the filing of the complaint. Inadvertently, the Commission scheduled the hearing after the expiration of the 120 days and the state courts held the requirement to be jurisdictional, necessitating dismissal of the complaint. The Court noted that various older cases had clearly established that causes of action were property, and, in any event, Logan’s claim was an entitlement grounded in state law and thus could only be removed “for cause.” This property interest existed independently of the 120-day time period and could not simply be taken away by agency action or inaction.833

The Liberty Interest.—With respect to liberty interests, the Court has followed a similarly meandering path. Although the traditional concept of liberty was freedom from physical restraint, the Court has expanded the concept to include various other protected interests, some statutorily created and some not.834 Thus, in Ingraham v. Wright,835 the Court unanimously agreed that school children had a liberty interest in freedom from wrongfully or excessively administered corporal punishment, whether or not such interest was protected by statute. “The liberty preserved from deprivation without due process included the right ‘generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.’ . . . Among the historic liberties so protected was a right to be free from, and to obtain judicial relief for, unjustified intrusions on personal security.”836

The Court also appeared to have expanded the notion of “liberty” to include the right to be free of official stigmatization, and found that such threatened stigmatization could in and of itself require due process.837 Thus, in Wisconsin v. Constantineau,838 the Court invalidated a statutory scheme in which persons could be labeled “excessive drinkers,” without any opportunity for a hearing and rebuttal, and could then be barred from places where alcohol was served. The Court, without discussing the source of the entitlement, noted that the governmental action impugned the individual’s reputation, honor, and integrity.839

But, in Paul v. Davis,840 the Court appeared to retreat from recognizing damage to reputation alone, holding instead that the liberty interest extended only to those situations where loss of one’s reputation also resulted in loss of a statutory entitlement. In Davis, the police had included plaintiff’s photograph and name on a list of “active shoplifters” circulated to merchants without an opportunity for notice or hearing. But the Court held that “Kentucky law does not extend to respondent any legal guarantee of present enjoyment of reputation which has been altered as a result of petitioners’ actions. Rather, his interest in reputation is simply one of a number which the State may protect against injury by virtue of its tort law, providing a forum for vindication of those interest by means of damage actions.”841 Thus, unless the government’s official defamation has a specific negative effect on an entitlement, such as the denial to “excessive drinkers” of the right to obtain alcohol that occurred in Constantineau, there is no protected liberty interest that would require due process.

A number of liberty interest cases that involve statutorily created entitlements involve prisoner rights, and are dealt with more extensively in the section on criminal due process. However, they are worth noting here. In Meachum v. Fano,842 the Court held that a state prisoner was not entitled to a fact-finding hearing when he was transferred to a different prison in which the conditions were substantially less favorable to him, because (1) the Due Process Clause liberty interest by itself was satisfied by the initial valid conviction, which had deprived him of liberty, and (2) no state law guaranteed him the right to remain in the prison to which he was initially assigned, subject to transfer for cause of some sort. As a prisoner could be transferred for any reason or for no reason under state law, the decision of prison officials was not dependent upon any state of facts, and no hearing was required.

In Vitek v. Jones,843 by contrast, a state statute permitted transfer of a prisoner to a state mental hospital for treatment, but the transfer could be effectuated only upon a finding, by a designated physician or psychologist, that the prisoner “suffers from a mental disease or defect” and “cannot be given treatment in that facility.” Because the transfer was conditioned upon a “cause,” the establishment of the facts necessary to show the cause had to be done through fair procedures. Interestingly, however, the Vitek Court also held that the prisoner had a “residuum of liberty” in being free from the different confinement and from the stigma of involuntary commitment for mental disease that the Due Process Clause protected. Thus, the Court has recognized, in this case and in the cases involving revocation of parole or probation,844 a liberty interest that is separate from a statutory entitlement and that can be taken away only through proper procedures.

But, with respect to the possibility of parole or commutation or otherwise more rapid release, no matter how much the expectancy matters to a prisoner, in the absence of some form of positive entitlement, the prisoner may be turned down without observance of procedures.845 Summarizing its prior holdings, the Court recently concluded that two requirements must be present before a liberty interest is created in the prison context: the statute or regulation must contain “substantive predicates” limiting the exercise of discretion, and there must be explicit “mandatory language” requiring a particular outcome if substantive predicates are found.846 In an even more recent case, the Court limited the application of this test to those circumstances where the restraint on freedom imposed by the state creates an “atypical and significant hardship.”847

Proceedings in Which Procedural Due Process Need Not Be Observed.—Although due notice and a reasonable opportunity to be heard are two fundamental protections found in almost all systems of law established by civilized countries,848 there are certain proceedings in which the enjoyment of these two conditions has not been deemed to be constitutionally necessary. For instance, persons adversely affected by a law cannot challenge its validity on the ground that the legislative body that enacted it gave no notice of proposed legislation, held no hearings at which the person could have presented his arguments, and gave no consideration to particular points of view. “Where a rule of conduct applies to more than a few people it is impracticable that everyone should have a direct voice in its adoption. The Constitution does not require all public acts to be done in town meeting or an assembly of the whole. General statutes within the state power are passed that affect the person or property of individuals, sometimes to the point of ruin, without giving them a chance to be heard. Their rights are protected in the only way that they can be in a complex society, by their power, immediate or remote, over those who make the rule.”849

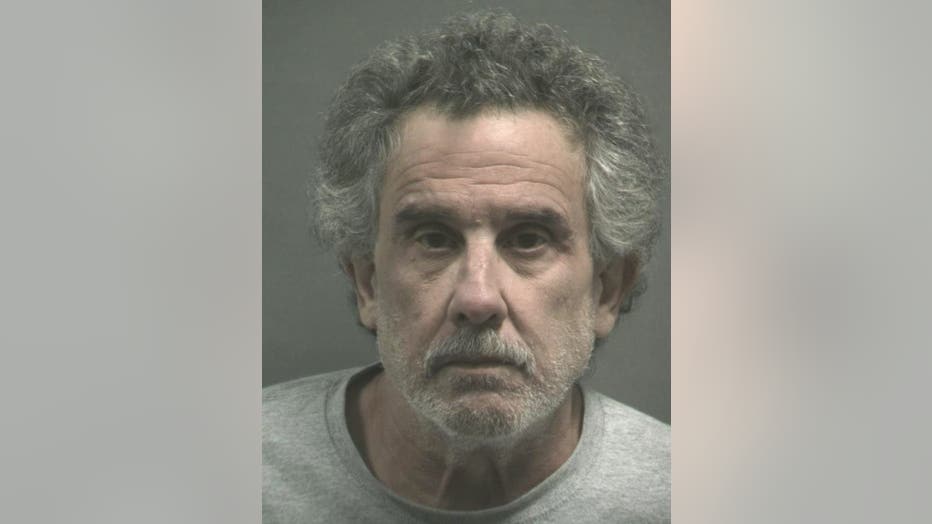

Man charged with punching flight attendant on Dallas flight also allegedly kicked officer in the groin

FBI: Man punched flight attendant, assaulted cop

A man accused of punching a flight attendant later kicked a police officer in the groin and spit on officers who were removing him from the plane in Texas, according to a newly released report by an FBI agent.

DALLAS – The FBI said a man who attacked a flight attendant on a trip out of Dallas continued attacking law enforcement even after they yanked him off the plane.

The allegations surfaced in newly revealed court documents.

Keith Edward Fagiana faces charges of interfering with a flight crew and could face up to 20 years in prison if convicted. He is scheduled to make his first federal court appearance Monday in Amarillo, which is where he was taken into custody after the flight was diverted there.

Keith Edward Fagiana

According to court records unsealed Friday, Fagiana told investigators he didn’t remember what happened.

Documents are revealing what led to the moment Wednesday when authorities in Amarillo pulled Fagiana off a flight from DFW Airport to Bozeman, Montana.

“My wife kind of started hitting me and saying, you know, getting me to pay attention that something was happening,” J.P. Gallagher recalled.

Gallagher, an elected official in Montana, was on the flight returning from vacation in Mexico with his wife and daughter.

“There was a drink cart between us and the incident. So I couldn’t see a lot what was going on, but I could hear some yelling and some, you know, cussing and, you know, the flight attendant saying, stop it,” Gallagher said.

According to a criminal complaint, it started when another passenger complained Fagiana was kicking their chair.

Dallas flight diverted over disruptive passenger

An American Airlines passenger faces criminal charges after reportedly assaulting a flight attendant. Keith Edward Fagiana allegedly assaulted a male flight attendant shortly after the flight departed from DFW Airport, bound for Bozeman, Montana.

When a flight attendant asked him to stop, authorities said “Fagiana then yelled expletives at the flight attendant and punched the flight attendant in the stomach,” before “Fagiana got up and punched the flight attendant three more times.”

The flight attendant and passengers were then able to restrain Fagiana and place flex cuffs on him.

Video taken by another passenger captured the confrontation with the flight attendant.

“Stop, stop, stop. What the (expletive) are you doing?” the flight attendant yelled at a man hitting him.

Related

Man arrested from diverted Dallas flight accused of assaulting flight attendant

An American Airlines passenger faces criminal charges after reportedly assaulting a flight attendant on a flight that departed from Dallas and was diverted to Amarillo.

“I was just paying attention to make sure that I didn’t see or hear anything about a weapon. You know, that was probably the most concerning thing,” Gallagher said.

The flight was diverted to Amarillo, where the FBI and local police were waiting.

Authorities said after they removed Fagiana, he “…complained to officers the flex cuffs were hurting him,” and “…while changing out handcuffs, Fagiana kicked one of the Amarillo Airport Police Officers in the groin area and spit on escorting officers.”

The FBI said Fagiana later claimed he didn’t remember anything that happened on the flight after drinking some Captain Morgans at bars in Las Vegas before the flight.

The union representing American’s flight attendants said in a statement: “…another Flight Attendant was assaulted by a customer. Our priority is to care for the affected crewmember. This violent behavior must stop.”

Passengers said the crew acted professionally throughout the ordeal.

“It’s sad, but you could tell that they had training and they were ready to respond to the incident that was going on,” Gallagher said.

Airlines reported more than 2,000 incidents of unruly passengers to the Federal Aviation Administration. That is down from a peak of nearly 6,000 in 2021, when far fewer people were traveling because of the pandemic.

The FAA said airlines reported 45 attacks by passengers on flight attendants last year.

In one of the most serious cases, a California woman was sentenced to 15 months in prison and ordered to pay nearly $26,000 in restitution for punching a Southwest Airlines flight attendant in the mouth and breaking her teeth.

The Associated Press contributed to this report

Passenger doesn’t remember punching flight attendant, forcing plane to divert; admits drinking ‘Captain Morgan’ before flying

Airport police take man off American Airlines Flight 1497 that was diverted to Amarillo on January 3, 2024. A passenger told ABC 7 that he punched a flight attendant (Credit: Dazia Poland)

0Comment

Share

AMARILLO, Texas (KVII) — The passenger who punched a flight attendant, forcing the plane to land in Amarillo, Texas, said he doesn’t remember what happened.

Keith Edward Fagiana is charged with interference with a flight crew.

According to the criminal complaint, Fagiana cursed at a male flight attendant and punched him four timesbefore he was tackled to the ground.

Around 1:50 p.m. Wednesday, American Airlines Flight 1497from Dallas to Bozeman declared a level two threat aboard the aircraft. The pilot said they were diverting to Rick Husband Amarillo International Airport.

When the plane landed at 2:20 p.m., Fagiana was taken into FBI custody.

The flight attendant told the FBI another passenger complained Fagiana was “violently kicking” their seat. When the flight attendant askedFagiana to stop,Fagiana “yelled expletives” at the flight attendant and punched him in the stomach. He then stood up and punched the flight attendant three more times.

Passengers confirmed what the flight attendant told them.

One of those passengers, Dazia Poland, shot a video of airport police taking Fagiana off the plane in handcuffs.

She shared the video with ABC 7 Amarillo.0.25×0.5xnormal1.5x2x

Airport police take man off American Airlines Flight 1497 that was diverted to Amarillo on January 3, 2024. A passenger told ABC 7 that he punched a flight attendant (Credit: Dazia Poland)

The flight attendant and other passengers tackledFagiana who was then placed in flex cuffs.

Fagiana told the FBI he did not remember anything that happened on the plane.

He admitted to drinking Captain Morgan rum at different bars in Las Vegas before the flight.

Before the interview,Fagiana complained the flex cuffs were hurting his wrists, so police agreed to switch them out for steel handcuffs.

When police took off the flex cuffs. Fagiana kicked an airport police officer in the groin and spit on other officers, according to the criminal complaint.

Fagiana said he did fight with the police officers because he didn’t want to be arrested.